You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

2020 Shelter in Place Alphabet Movie Draft - BONUS ROUNDS

- Thread starter Jack Jack

- Start date

bajaden

Hall of Famer

D = Dead Calm: This is another of my favorite little movies, where you sit down with your peanuts, or a bowl of Cheeto's and your favorite beverage. First time around, it will keep you on the edge of your seat. This was an Australian production and was directed by Phillip Noyce. It stars Sam Neill, Nicole Kidman, and Billy Zane. It was one of the last films that Kidman made in her home country of Australia before becoming a star in the United States. Personally, I'll watch any movie that has Sam Neill in it. There's a reason he's been around since the last ice age.

Rae Ingram (Nicole Kidman) is involved in a car crash which results in the death of her son. Her older husband, Royal Australian Navy officer John Ingram (Sam Neill), suggests that they help deal with their grief by heading out for a vacation alone on their yacht. In the middle of the Pacific, they encounter a drifting boat that seems to be taking on water. A man, Hughie Warriner (Billy Zane), rows over to the Ingrams' boat for help. He claims that his boat is sinking and that his companions have all died of food poisoning.

Suspicious of Hughie's story, John rows over to the other ship, leaving Rae alone with Hughie. Inside, John discovers the mangled corpses of the other passengers and video footage indicating that Hughie may have murdered them in a feat of extraordinary violence. John rushes back to his own boat, but he's too late as Hughie awakes, knocks out Rae and sails their yacht away, leaving John behind.

Rae Ingram (Nicole Kidman) is involved in a car crash which results in the death of her son. Her older husband, Royal Australian Navy officer John Ingram (Sam Neill), suggests that they help deal with their grief by heading out for a vacation alone on their yacht. In the middle of the Pacific, they encounter a drifting boat that seems to be taking on water. A man, Hughie Warriner (Billy Zane), rows over to the Ingrams' boat for help. He claims that his boat is sinking and that his companions have all died of food poisoning.

Suspicious of Hughie's story, John rows over to the other ship, leaving Rae alone with Hughie. Inside, John discovers the mangled corpses of the other passengers and video footage indicating that Hughie may have murdered them in a feat of extraordinary violence. John rushes back to his own boat, but he's too late as Hughie awakes, knocks out Rae and sails their yacht away, leaving John behind.

Löwenherz

Starter

D = Dead Calm: This is another of my favorite little movies, where you sit down with your peanuts, or a bowl of Cheeto's and your favorite beverage. First time around, it will keep you on the edge of your seat. This was an Australian production and was directed by Phillip Noyce. It stars Sam Neill, Nicole Kidman, and Billy Zane. It was one of the last films that Kidman made in her home country of Australia before becoming a star in the United States. Personally, I'll watch any movie that has Sam Neill in it. There's a reason he's been around since the last ice age.

Rae Ingram (Nicole Kidman) is involved in a car crash which results in the death of her son. Her older husband, Royal Australian Navy officer John Ingram (Sam Neill), suggests that they help deal with their grief by heading out for a vacation alone on their yacht. In the middle of the Pacific, they encounter a drifting boat that seems to be taking on water. A man, Hughie Warriner (Billy Zane), rows over to the Ingrams' boat for help. He claims that his boat is sinking and that his companions have all died of food poisoning.

Suspicious of Hughie's story, John rows over to the other ship, leaving Rae alone with Hughie. Inside, John discovers the mangled corpses of the other passengers and video footage indicating that Hughie may have murdered them in a feat of extraordinary violence. John rushes back to his own boat, but he's too late as Hughie awakes, knocks out Rae and sails their yacht away, leaving John behind.

Hey Hey, good ole Brickie took that same one as his last pick. Never knew it had such a rich and elaborate history before his pick. Now I’m kind of fascinated by it.

Now, I've got to listen to that, again.

As my third "free pick" in the alphabetical movie draft, I select:

Limelight (1952)

Directed by Charlie Chaplin

Starring Charlie Chaplin, Claire Bloom, Buster Keaton (cameo)

Trailer

Charlie Chaplin is best known for his character known as The Tramp, who Chaplin portrayed in numerous silent films between 1914 and 1936. It's hit-and-miss stuff for modern audiences, but it's what Chaplin was known for, so I bring it up.

Limelight is NOT a Tramp film. It's a much more serious take, wherein Chaplin (at the age of 63) plays the old, drunken, washed-up former Vaudeville stage star Calvero who happens upon a young ballerina attempting suicide, and saves her. After getting her straight he sets her back into her dancing career, which takes off as he tries unsuccessfully to rekindle his former stage glory...

Limelight is a relatively obscure film, especially compared to Chaplin's Tramp classics, but for me it's a finer film in every way. It's a sentimental story, but a good one, and one that feels true. Although I've no proof, I'm convinced that Limelight was the inspiration for a film that I picked in the previous movie draft, which also features a fading star entertainer of a dead genre giving a leg up to a rising star in the new genre. And with that, I'm up to 30 films that are sure to keep me quite entertained on my mostly-alphabetical island.

That's all any of us are: amateurs. We don't live long enough to be anything else.

Time is the best author. It always writes the perfect ending.

Limelight (1952)

Directed by Charlie Chaplin

Starring Charlie Chaplin, Claire Bloom, Buster Keaton (cameo)

Trailer

Charlie Chaplin is best known for his character known as The Tramp, who Chaplin portrayed in numerous silent films between 1914 and 1936. It's hit-and-miss stuff for modern audiences, but it's what Chaplin was known for, so I bring it up.

Limelight is NOT a Tramp film. It's a much more serious take, wherein Chaplin (at the age of 63) plays the old, drunken, washed-up former Vaudeville stage star Calvero who happens upon a young ballerina attempting suicide, and saves her. After getting her straight he sets her back into her dancing career, which takes off as he tries unsuccessfully to rekindle his former stage glory...

Limelight is a relatively obscure film, especially compared to Chaplin's Tramp classics, but for me it's a finer film in every way. It's a sentimental story, but a good one, and one that feels true. Although I've no proof, I'm convinced that Limelight was the inspiration for a film that I picked in the previous movie draft, which also features a fading star entertainer of a dead genre giving a leg up to a rising star in the new genre. And with that, I'm up to 30 films that are sure to keep me quite entertained on my mostly-alphabetical island.

That's all any of us are: amateurs. We don't live long enough to be anything else.

Time is the best author. It always writes the perfect ending.

Jack Jack

G-League

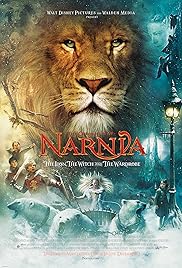

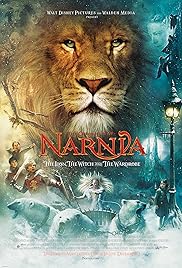

C = The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe (2005)

Link #1 = Trailer

Link #2 = Beaver's Dam

Link #3 = Battle for Narnia

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0363771/?ref_=nv_sr_srsg_0

Roger Ebert said:C. S. Lewis, who wrote the Narnia books, and J.R.R. Tolkien, who wrote the Ring trilogy, were friends who taught at Oxford at the same time, were pipe-smokers, drank in the same pub, took Christianity seriously, but although Lewis loved Tolkein’s universe, the affection was not returned. Well, no wonder. When you’ve created your own universe, how do you feel when, in the words of a poem by e. e. cummings:: "Listen: there's a hell/of a good universe next door; let's go."

Tolkien's universe was in unspecified Middle Earth, but Lewis' really was next door. In the opening scenes of "The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe," two brothers and two sisters from the Pevensie family are evacuated from London and sent to live in a vast country house where they will be safe from the nightly Nazi air raids. Playing hide-and-seek, Lucy, the youngest, ventures into a wardrobe that opens directly onto a snowy landscape where before long Mr. Tumnus is explaining to her that he is a faun.

Fauns, like leprechauns, are creatures in the public domain, unlike Hobbits, who are under copyright. There are mythological creatures in Narnia, but most of the speaking roles go to humans like the White Witch (if indeed she is human) and animals who would be right at home in the zoo (if indeed they are animals). The kids are from a tradition which requires that British children be polite and well-spoken, no doubt because Lewis preferred them that way. What is remarkable is that this bookish bachelor who did not marry until he was nearly 60 would create four children so filled with life and pluck.

That's the charm of the Narnia stories: They contain magic and myth, but their mysteries are resolved not by the kinds of rabbits that Tolkien pulls out of his hat, but by the determination and resolve of the Pevensie kids -- who have a good deal of help, to be sure, from Aslan the Lion. For those who read the Lewis books as a Christian parable, Aslan fills the role of Christ because he is resurrected from the dead. I don't know if that makes the White Witch into Satan, but Tilda Swinton plays the role as if she has not ruled out the possibility.

The adventures that Lucy has in Narnia, at first by herself, then with her brother Edmund and finally with the older Peter and Susan, are the sorts of things that might happen in any British forest, always assuming fauns, lions and witches can be found there, as I am sure they can. Only toward the end of this film do the special effects ramp up into spectacular extravaganzas that might have caused Lewis to snap his pipe stem.

It is the witch who has kept Narnia in frigid cold for a century, no doubt because she is descended from Aberdeen landladies. Under the rules, Tumnus (James McAvoy) is supposed to deliver Lucy (Georgie Henley) to the witch forthwith, but fauns are not heavy hitters, and he takes mercy. Lucy returns to the country house and pops out of the wardrobe, where no time at all has passed and no one will believe her story. Edmund (Skandar Keynes) follows her into the wardrobe that evening and is gob-smacked by the White Witch, who proposes to make him a prince.

But Peter (William Moseley) and Susan (Anna Popplewell) don’t believe Lucy until all four children tumble through the wardrobe into Narnia. They meet the first of the movie's CGI-generated characters, Mr. and Mrs. Beaver (voices by Ray Winstone and Dawn French), who invite them into their home, which is delightfully cozy for being made of largish sticks. The Beavers explain the Narnian situation to them, just before an attack by computerized wolves whose dripping fangs reach hungrily through the twigs.

Edmund by now has gone off on his own and gotten himself taken hostage, and the Beavers hold out hope that perhaps the legendary Aslan (voice by Liam Neeson) can save him. This involves Aslan dying for Edmund's sins, much as Christ died for ours. Aslan's eventual resurrection leads into an apocalyptic climax that may be inspired by Revelation. Since there are six more books in the Narnia chronicles, however, we reach the end of the movie while still far from the Last Days.

These events, fantastical as they sound, take place on a more human, or at least more earthly, scale than those in "Lord of the Rings." The personalities and character traits of the children have something to do with the outcome, which is not being decided by wizards on another level of reality but will be duked out right here in Narnia. That the battle owes something to Lewis' thoughts about the first two world wars is likely, although nothing in Narnia is as horrible as the trench warfare of the first or the Nazis of the second.

The film has been directed by Andrew Adamson, who directed both of the "REDACTED" movies and supervised the special effects on both of Joel Schumacher's "REDACTED" movies. He knows his way around both comedy and action, and here combines them in a way that makes Narnia a charming place with fearsome interludes. We suspect that the Beavers are living on temporary reprieve and that wolves have dined on their relatives, but this is not the kind of movie where you bring up things like that.

C.S. Lewis famously said he never wanted the Narnia books to be filmed because he feared the animals would "turn into buffoonery or nightmare." But he said that in 1959, when he might have been thinking of a man wearing a lion suit, or puppets.

The effects in this movie are so skillful that the animals look about as real as any of the other characters, and the critic Emanuel Levy explains the secret: "Aslan speaks in a natural, organic manner (which meant mapping the movement of his speech unto the whole musculature of the animal, not just his mouth)." Aslan is neither as frankly animated as the REDACTED or as real as the cheetah in "REDACTED," but halfway in between, as if an animal were inhabited by an archbishop.

This is a film situated precisely on the dividing line between traditional family entertainment and the newer action-oriented family films. It is charming and scary in about equal measure, and confident for the first two acts that it can be wonderful without having to hammer us into enjoying it, or else. Then it starts hammering. Some of the scenes toward the end push the edge of the PG envelope, and like the "Harry Potter" series, the Narnia stories may eventually tilt over into R. But it's remarkable, isn't it, that the Brits have produced Narnia, the Ring, Hogwarts, Gormenghast, James Bond, Alice and Pooh, and what have we produced for them in return? I was going to say "the cuckoo clock," but for that you would require a three-way Google of Italy, Switzerland and Harry Lime.

Link #1 = Trailer

Link #2 = Beaver's Dam

Link #3 = Battle for Narnia

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0363771/?ref_=nv_sr_srsg_0

Löwenherz

Starter

In some ways my next pick hasn't aged well, essentially marking ground zero for the heavy bloat of Frat Pack comedies in the aughts.

Yet viewed in a vacuum, it's clever, heartfelt, observant, smooth, chill, and timeless.

Baby, this movie is so money and you don't even know it, man.

Wildcard #3 is for ...

Swingers (1996)

All right, so classic rookie year Vince Vaughn in a role perfectly showcasing his specific talents at their absolute peek. In the years that followed Vaughn would be chained to the typecast, becoming something of a self-parody, slavishly delivering they "cocky, fast talking, street smart" guy's guy in a cavalcade of comedies. But in Swingers it was fresh and perfectly proportioned throughout the narrative.

But that's just the door prize. Inside there is the hypnotic tour of the mid-90s LA singles scene that is part satire, but also rather effective at selling the lifestyle as something exciting and fun. The bar-hoping universe of the Hollywood Swingers is shallow, misogynistic even. Yet, there's depth and logic to the rules, and if you squint an asymmetrical power of the sexes below the surface.

At the core of it all is a legitimately sweet "bro code" story of male bonding, in which the fake LA players show legitimate concern and empathy for their friend struggling with a heartbreak. Their support may appear strange, self-serving, and maybe a little counter-productive and possibly even destructive. But it's their honest attempt to help carry their friend past the universal hurt of a break-up, no matter how many times they need to make Wayne Gretzky's head bleed to do it.

That's it everyone. I'm on my way out. But no worries ...

This place was dead anyway.

Yet viewed in a vacuum, it's clever, heartfelt, observant, smooth, chill, and timeless.

Baby, this movie is so money and you don't even know it, man.

Wildcard #3 is for ...

Swingers (1996)

All right, so classic rookie year Vince Vaughn in a role perfectly showcasing his specific talents at their absolute peek. In the years that followed Vaughn would be chained to the typecast, becoming something of a self-parody, slavishly delivering they "cocky, fast talking, street smart" guy's guy in a cavalcade of comedies. But in Swingers it was fresh and perfectly proportioned throughout the narrative.

But that's just the door prize. Inside there is the hypnotic tour of the mid-90s LA singles scene that is part satire, but also rather effective at selling the lifestyle as something exciting and fun. The bar-hoping universe of the Hollywood Swingers is shallow, misogynistic even. Yet, there's depth and logic to the rules, and if you squint an asymmetrical power of the sexes below the surface.

At the core of it all is a legitimately sweet "bro code" story of male bonding, in which the fake LA players show legitimate concern and empathy for their friend struggling with a heartbreak. Their support may appear strange, self-serving, and maybe a little counter-productive and possibly even destructive. But it's their honest attempt to help carry their friend past the universal hurt of a break-up, no matter how many times they need to make Wayne Gretzky's head bleed to do it.

That's it everyone. I'm on my way out. But no worries ...

This place was dead anyway.

Last edited:

Swingers (1996)

"Did you just walk in or were you listening all along?"

"Don't ever call me again."

Löwenherz

Starter

"Did you just walk in or were you listening all along?"

"Don't ever call me again."

Like watching a guy get crushed to death by a Zamboni machine he could easily avoid if he just walked off the ice.

Last edited:

Padrino

All-Star

With my thirtieth and final pick in the Shelter in Place Alphabet Movie Draft, I will make use of the letter T once again to select:

There Will Be Blood (2007):

Director: Paul Thomas Anderson

Dir. of Photography: Robert Elswit

Writer: Paul Thomas Anderson, Upton Sinclair (based on the novel Oil!, by)

Score: Jonny Greenwood

Cast: Daniel Day-Lewis, Paul Dano, Dillon Freasier, Ciarán Hinds, Kevin J. O'Connor

Genre: Drama

Runtime: 2 hours, 38 minutes

IMDb Entry: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0469494/?ref_=nv_sr_srsg_0

I began this draft with my favorite film of all time, and I am ending with the single greatest film of this young millennium, featuring the most thrilling lead performance in a career of thrilling lead performances by Daniel Day-Lewis as Daniel Plainview, an entrepreneur making his name in the oil business in PTA's feverish capitalist nightmare.

https://www.slantmagazine.com/film/drilling-for-art-there-will-be-blood-take-1/

There Will Be Blood (2007):

Director: Paul Thomas Anderson

Dir. of Photography: Robert Elswit

Writer: Paul Thomas Anderson, Upton Sinclair (based on the novel Oil!, by)

Score: Jonny Greenwood

Cast: Daniel Day-Lewis, Paul Dano, Dillon Freasier, Ciarán Hinds, Kevin J. O'Connor

Genre: Drama

Runtime: 2 hours, 38 minutes

IMDb Entry: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0469494/?ref_=nv_sr_srsg_0

I began this draft with my favorite film of all time, and I am ending with the single greatest film of this young millennium, featuring the most thrilling lead performance in a career of thrilling lead performances by Daniel Day-Lewis as Daniel Plainview, an entrepreneur making his name in the oil business in PTA's feverish capitalist nightmare.

Matt Zoller Seitz said:Paul Thomas Anderson’s epic drama There Will Be Blood—in which Daniel Day-Lewis’ prospector-turned-robber baron antihero, Daniel Plainview, pick-axes his way toward an oil fortune—isn’t perfect or entirely satisfying, but it’s so singular in its conception and execution that one can no more dismiss it than one can dismiss a volcanic eruption occurring in one’s backyard.

It cannot be diminished—as Hard Eight, Boogie Nights and Magnolia could, and to my mind, rightly were diminished—as another instance of a facile, energetic director hurling homage at the audience.

In Blood, as in Anderson’s fourth, most distinctively original feature, 2002’s Punch-Drunk Love, the director lays his influences on the table (in plain view, as it were). But he isn’t content to quote and rearrange with his usual hyperkinetic fussiness. There are moments, scenes, and an entire section that I think veer out of control, and not in a good way. But for the most part, Anderson seems to have absorbed his influences and created a singular work; there are so few tonal or dramatic miscalculations—and so few reversions to the cinematic karaoke machine mode of his first three pictures—that when one does pop up, it’s a such a shock that it takes you out of the movie. From the opening section, in which Daniel the prospector finds and stakes a crude oil claim and inherits the young son of a worker who died in his employ, through the complex, moving, frequently upsetting midsection that depicts Daniel amassing his fortune, acquiring and betraying allies, out-thinking and sometimes terrorizing his rivals, and destroying people he should treasure, Blood becomes as pointed a critique (and celebration) of capitalism as the Godfather movies—and other things besides.

For a decade now, ever since his second feature, Boogie Nights exploded onto screens like a string of Chinese firecrackers, Paul Thomas Anderson has been American cinema’s giant-in-waiting—a self-taught writer-director-impresario-icon who aimed to be not just the last great 1970s filmmaker, but all of them rolled into one: Altman, Cassavetes, Scorsese, Coppola, Penn, Demme, Ashby and many, many more. In Hard Eight, Boogie Nights and Magnolia, he cherry-picked situations, setpieces, even particular shots from his heroes’ movies and re-imagined them (or sometimes simply regurgitated them). I was among his early detractors, admiring but not quite embracing Hard Eight, and finding Boogie Nights and Magnolia almost insufferably imitative, superficial and self-satisfied. His second and third films, in particular, were spectacularly inconsistent. Flamboyant camerawork, jigsaw-puzzle montages and scripted-to-the-commas dialogue jostled against actor’s workshop hysterics and amateurishly improvised banter, and both films’ midsections seemed glommed together with gaffer’s tape. At times Anderson reminded me of another deeply musical but often incoherent director, Spike Lee: his films played like grandiose ‘60s/‘70s double albums, comprised of finely wrought singles and jam session filler held together by nerve.

Yet parts of all of his features amused, enthralled or moved me. Magnolia’s go-to shot—a vertigo-inducing whip-pan that became a combination high speed dolly-in/zoom-in; a shot so closely identified with Goodfellas that any director who uses it might as well stamp “Property of Martin Scorsese” at the bottom of the frame—was a trite signifier of energy, and there was too much yelling, stammering and sobbing in place of acting; but the movie was shot through with visionary sequences (the “Wise Up” musical interlude; the rain of frogs) and surprising, affecting performances (by Tom Cruise, Melora Walters, William H. Macy, Jason Robards and Melinda Dillon especially). Half of Boogie Nights made me wish I was at home watching Raging Bull, Saturday Night Fever, Midnight Cowboy or any of the other touchstones that Anderson made sure we all knew he’d seen; the rest—especially the scenes that focused on someone besides the horse-hung Candide, Dirk Diggler—was as sweet and unsettling as its influences. Was Anderson a fearsome impressionist, or an original talent who had not yet found his true voice? After seeing Punch-Drunk Love, I figured it was the latter. For the first time, Anderson had applied his virtuoso technique, his rapport with actors and his archivist’s memory to a film that was impossible to dismiss as pastiche. The merger of Anderson’s droll wit and long-take choreography and Sandler’s agitated man-child shtick sparked an alchemical reaction; Love was so peculiar that it could indulge in baldfaced shout-outs (most notoriously in the madcap montage scored to “He Needs Me,” from Popeye) without breaking its obnoxious, endearing spell. Was it possible that his first three films constituted nine hours of throat-clearing?

Yes. As muscular and restless as it is, Blood demonstrates greater discipline and confidence than anything Anderson has made—a willingness to hang back, to let scenes play without editorializing music or at medium or long distance; a sense of when it’s desirable to generate excitement mainly through camera movement, cutting, sound design and other overt means, and when such intervention would prove superfluous or reductive. The film’s virtually score-free 1902 prologue, which shows a younger, bearded Daniel rappelling into a cavern in search of precious metal, is photographed (by Robert Elswit) with what Pauline Kael, reviewing Spike Lee’s debut, She’s Gotta Have It, called “a film sense.” Daniel’s dangling, scrambling figure and certain significant rock formations are etched with enough light to allow viewers to orient themselves along with the hero, but not so much that you lose the sense of primordial gloom; the outlining is subjective, a means of suggesting what the hero senses but can’t see. Daniel is relentless, but the work is difficult, the conditions brutal. Like the combat scenes in The Thin Red Line, with their incongruous cutaways to bored-looking animals, and the long section in Cast Away, in which the starving hero teaches himself how to acquire, open and devour a coconut, the first section of Blood reminds 21st century multiplex audiences that the natural world could not care less what humanity wants.

This inaugural setpiece segues neatly into a scene showing Daniel and a crew drilling for oil, which Daniel deduces is the region’s true motherlode. The sense of exertion and exhaustion is even more pronounced (and frightening) because Daniel has drawn other people into his obsession and seems to have as little regard for their safety as he does for his own. The film adopts the hero’s single-minded point-of-view. When a man is injured or killed, Anderson shows what happened and how the crew moved on from there, as if recounting what became of a broken pickax. Daniel’s commitment is scientific in its problem-solving acuity, demonic in its refusal of defeat. In its mix of dynamic need and utilitarian methodology—its understanding of how visionary businessmen regard workers as sentient tools—this may be the finest sequence Anderson has directed. And it subtly sets up the film’s symbolic architecture: its recurring images of men rising (physically or metaphorically) and then falling, complemented by the rising and falling motion of oil derricks, and the rising, falling movement of Elswit’s camera as it rises up over ridges along with Daniel to reveal new territories he intends to acquire. When, towards the end of the first cave sequence, an agonized Daniel hauls himself up toward the surface, Elswit’s camera tilting up to reveal the exit, the sun bursting through the hole feels not reassuring but taunting. Daniel would rather be down in the dark.

The bulk of Blood, set in 1911, follows Daniel as he methodically and sometimes sneakily builds his fortune, accompanied at each step by his adopted son, H.W. (played as a preadolescent by Dillon Freasier). Anderson’s book is based on Upton Sinclair’s Oil!, which he’s said he encountered by chance in a London bookstore, but this source is just a springboard for a tale that owes as much, if not more, to other prominent sources: Erich von Stroheim’s Greed (likewise a story of a man sacrificing love on the altar of money); Citizen Kane (ditto); the Godfather trilogy (ditto again); the collected works of Stanley Kubrick, specifically Barry Lyndon and the four-movement cosmic spectacle 2001 (a source whose kinship to Blood Filmbrain nicely analyzes here). They all feed Anderson’s fever.

The film is ultimately not as emotionally rich and all-encompassing as those touchstones because it mostly sticks with Daniel, a closed-off man who seems to have little soul to lose, and syncs up his lordly ruthlessness and the director’s style, robbing the film of the greater complexity it might have achieved from having the hero and the style work at cross-purposes (and they surely would have in a film by Altman or Terrence Malick). From the moment we meet Daniel, he’s a terrifying capitalist instrument, telegraphing his objectives (to the viewer, his clients and his rivals) so unambiguously (and with a rumbling, often gleeful voice) that at times he evokes John Huston’s Noah Cross from Chinatown. Between Day-Lewis’ hyperreal performance—always teetering on the edge of theatrical artifice—and Jonny Greenwood’s aggressively dissonant score, Daniel radiates an almost vampiric mix of hunger, patience and indestructibility; midway through the movie, when he’s riding on a train and a shaft of sunlight unexpectedly hits his face, I half-expected him to burst into flame. Yet in characterizing Daniel, here too Anderson mostly transcends his influences, creating a character we haven’t seen before in a movie that feels fresh. Daniel is inarguably kin to Michael Corleone and Charles Foster Kane—a monster of ego, manipulative, ruthless and self-loathing. But there’s more here than Lonely Capitalist cliche. Daniel has human potential, but it can’t be tapped because his drive is so intense and his emotional armor so thick. You can see it in the way that Daniel dotes on H.W. during their initial train ride together in the 1902 sequence. Even though he’s probably already thinking of ways he can amortize this profound emotional investment—sure enough, in the 1911 section H.W. accompanies Daniel on business meetings, enabling Daniel to declare, “I’m a family man” before he commences screwing whoever he’s dealing with—from the start, the connection between boy and man seems intuitive, elemental, real. Later in the film, after Daniel has used and neglected H.W. and then coldly sent him packing, there still seems to be real love there, however mangled. Later, when the newly-returned H.W. walks through a field with Daniel, who is spouting the usual self-justifying bullcrap and otherwise acting as if he’s done nothing wrong, the boy hauls off and starts slapping him. Anderson’s directorial detachment—framing the whole exchange in long shot—is masterful.

Daniel’s relationship with a young preacher, Eli Sunday (Paul Dano), is less perfectly realized, though to be fair it’s much more tangled and overtly archetypal than the Daniel-H.W. relationship, conceived both realistically and schematically. Eli enters Daniel’s life as a potential business contact, bringing Daniel news of his family’s oil-rich property in the town of New Boston; as the years wear on, establishing New Boston as the wellspring of Daniel’s wealth and Daniel as the driving force behind the town’s evolution, the prospector and the reverend become locked in an unending contest of wills, each trying to force the other to bend. It’s hard to say who started it—probably Daniel, who correctly sized up Eli as a young man out of his depth and acquired drilling rights for less than they were worth. The relationship gives the movie its dramatic backbone and sets up a number of terrific moments, most of them tending toward black comedy, the “confession” that Eli coerces out of Daniel being an especially satisfying example. (You know that the kid concocted the situation not to save Daniel’s soul, but to force a strong man to literally kneel, then slap him around in public without fear of retribution.)

Anderson’s attitude toward faith is conflicted, maybe muddled. Here, as in Magnolia, he seems fascinated by piety as a character trait, or a pretext to stage biblically spectacular events or iconic shots of people praying in the vicinity of crucifixes. He’s not nearly as interested in faith’s effect on daily life or the construction of personality. While Eli’s fervor is real, it seems to have less to do with faith per se than with his desire to establish dominance over Daniel. It’s religion-as-racket: Eli is a parasite who has attached himself to a dominant predator (essentially shaking down Daniel for money or prestige) while presenting himself, and almost certainly seeing himself, as a doer of good deeds. Compared to Daniel’s obsession with profit and control of land, which is destructive and self-destructive but at least honest, Eli’s faith carries with it a powerful whiff of hypocrisy; the reverend’s angelic face and polite demeanor notwithstanding (Dano is terrific), his character doesn’t quite transcend the stock conception of the preacher man playing an angle. He’s like the corrupt senators, police captains and other public officials in the Godfather films whose soulless rapaciousness was intended to make Coppola’s mafiosi seem like paragons of dark integrity. The true religion here is profit. Anderson treats the pursuit of entrepreneurship as an unholy (but to practitioners, holy) calling. Blood starts with a black screen, backed by a souls-in-torment Greenwood cue that could be Hell’s orchestra tuning up; as the music rises in volume and pitch, building to a sonic eruption, Anderson fades to blinding white, then fades the brightness back down to take us into the first digging sequence. Here and elsewhere in the opening section, the mix of Greenwood’s atonal cues and the architecturally-framed shots of rock formations and jagged hills evokes (intentionally, I’m sure) Close Encounters, another secular blockbuster spiked with religious motifs and populated by ordinary people afflicted with visionary drives. (Beyond its sci-fi and religious aspects, Close Encounters was a metaphoric working-through of Steven Spielberg’s compulsion to realize his fantasies on celluloid, even if it meant sacrificing domestic happiness and letting the world think him mad. Blood invites similar comparisons between its director and main character, a driven, innovative autocrat who likes getting his hands dirty, knows his trade better than anyone, and desires patrons, not partners.)

What saves the Eli-Daniel antagonism from allegorical preciousness (Commerce vs. Religion, step right up!) is Anderson’s sense of absurdity—arguably the most original and potent aspect of his talent. The preacher and the businessman go at each other like cartoon foes. Their showdowns and negotiations are grotesque and funny—Daniel, in particular, seems to enjoy putting the screws to Eli. Yet the finale and the buildup to it make the film seem like an epic pissing match when all things considered, it could have been, and arguably is, more than that.

...

https://www.slantmagazine.com/film/drilling-for-art-there-will-be-blood-take-1/

Gimli: This new Gandalf is more grumpy than the old one.

The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers (Extended Edition, 2002)

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0167261/

The Lord of the Rings trilogy is one of the most ambitious acts of filmmaking ever attempted - and was pulled off fairly brilliantly by Peter Jackson. While I took the third film in the last draft, this movie fills a different kind of "epic" (226 minute runtime!) film itch - with some of the best battle scenes ever put to film. Emotionally hefty and beautifully filmed, I'm glad to be able to take this with my final pick. One issue I had with the first and third films was the length, as in some parts were dragged out a little longer than they really needed to be. There is much less of that here (except some parts with Gollum). But the films are so well done even that doesn't really detract from the spectacle and experience.

Gandalf's battle with the Balrog, the flee to Helm's Deep from Edoras, the Ent battle at Isengard, and, of course, the battle at Helm's Deep - these and more are intricately woven into a masterpiece of filmmaking. Of course, the battle at Helm's Deep is the proverbial cherry on top of the whole mountain of peanut butter and chocolate ice cream and brownie sundae (with whipped cream!) goodness.

From wikipedia:

Gimli: Oh come on, we can take 'em.

Aragorn: It's a long way.

Gimli: Toss me.

Aragorn: What?

Gimli: I cannot jump the distance, you'll have to toss me.

Gimli: [pauses, looks up at Aragorn]

Gimli: Don't tell the Elf.

Aragorn: Not a word.

Gandalf: [to Grima] Be silent. Keep your forked tongue behind your teeth. I did not pass through fire and death to bandy crooked words with a witless worm.

Aragorn: Gimli, lower your axe.

Legolas: They have feelings, my friend. The elves began it, waking up the trees, teaching them to speak.

Gimli: Talking trees. What do trees have to talk about, hmm... except the consistency of squirrel droppings?

Haldir: I bring word from Lord Elrond of Rivendell. An Alliance once existed between Elves and Men. Long ago we fought and died together. We come to honor that allegiance.

Aragorn: Mae govannen, Haldir. You are most welcome.

Haldir: We are proud to fight alongside Men once more.

Treebeard: You must understand, young Hobbit, it takes a long time to say anything in Old Entish. And we never say anything unless it is worth taking a long time to say.

Treebeard: [after seeing the torn-down forest around Isengard] Saruman! A wizard should know better! There is no curse in Elvish, Entish, or the tongues of men for this treachery.

Pippin: Look, the trees! They're moving!

Merry: Where are they going?

Treebeard: They have business with the Orcs. My business is with Isengard tonight, with rock and stone.

[Ents emerge from the woods, following Treebeard]

Treebeard: Hroom, hm, come, my friends. The Ents are going to war. It is likely that we go to our doom. The last march of the Ents.

Gimli: [to a Warg] Bring your pretty face to my axe.

Gandalf: Three hundred lives of men I have walked this earth and now I have no time.

Gandalf: The battle of Helm's Deep is over; the battle for Middle-Earth is about to begin.

The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers (Extended Edition, 2002)

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0167261/

The Lord of the Rings trilogy is one of the most ambitious acts of filmmaking ever attempted - and was pulled off fairly brilliantly by Peter Jackson. While I took the third film in the last draft, this movie fills a different kind of "epic" (226 minute runtime!) film itch - with some of the best battle scenes ever put to film. Emotionally hefty and beautifully filmed, I'm glad to be able to take this with my final pick. One issue I had with the first and third films was the length, as in some parts were dragged out a little longer than they really needed to be. There is much less of that here (except some parts with Gollum). But the films are so well done even that doesn't really detract from the spectacle and experience.

Gandalf's battle with the Balrog, the flee to Helm's Deep from Edoras, the Ent battle at Isengard, and, of course, the battle at Helm's Deep - these and more are intricately woven into a masterpiece of filmmaking. Of course, the battle at Helm's Deep is the proverbial cherry on top of the whole mountain of peanut butter and chocolate ice cream and brownie sundae (with whipped cream!) goodness.

From wikipedia:

The film features an ensemble cast including Elijah Wood, Ian McKellen, Liv Tyler, Viggo Mortensen, Sean Astin, Cate Blanchett, John Rhys-Davies, Bernard Hill, Christopher Lee, Billy Boyd, Dominic Monaghan, Orlando Bloom, Hugo Weaving, Miranda Otto, David Wenham, Brad Dourif, Karl Urban and Andy Serkis.

Continuing the plot of The Fellowship of the Ring, the film intercuts three storylines. Frodo and Sam continue their journey towards Mordor to destroy the One Ring, meeting and joined by Gollum, the ring's former owner. Aragorn, Legolas, and Gimli come to the war-torn nation of Rohan and are reunited with the resurrected Gandalf, before fighting against the legions of the treacherous wizard Saruman at the Battle of Helm's Deep. Merry and Pippin escape capture, meet Treebeard the Ent, and help to plan an attack on Isengard, fortress of Saruman.

The Battle of Helm's Deep has been named as one of the greatest screen battles of all time.

The film was highly acclaimed by critics and fans alike, who considered it to be a landmark in filmmaking and an achievement in the fantasy film genre. It grossed $951.2 million worldwide, making it the highest-grossing film of 2002 and the third highest-grossing film of all time at the time of its release.

The Two Towers is widely regarded as one of the greatest and most influential films ever made. The film received numerous accolades; at the 75th Academy Awards, it was nominated for six awards, including Best Picture, Best Art Direction, Best Film Editing and Best Sound Mixing, winning two: Best Sound Editing and Best Visual Effects.

Gimli: Oh come on, we can take 'em.

Aragorn: It's a long way.

Gimli: Toss me.

Aragorn: What?

Gimli: I cannot jump the distance, you'll have to toss me.

Gimli: [pauses, looks up at Aragorn]

Gimli: Don't tell the Elf.

Aragorn: Not a word.

Gandalf: [to Grima] Be silent. Keep your forked tongue behind your teeth. I did not pass through fire and death to bandy crooked words with a witless worm.

Aragorn: Gimli, lower your axe.

Legolas: They have feelings, my friend. The elves began it, waking up the trees, teaching them to speak.

Gimli: Talking trees. What do trees have to talk about, hmm... except the consistency of squirrel droppings?

Haldir: I bring word from Lord Elrond of Rivendell. An Alliance once existed between Elves and Men. Long ago we fought and died together. We come to honor that allegiance.

Aragorn: Mae govannen, Haldir. You are most welcome.

Haldir: We are proud to fight alongside Men once more.

Treebeard: You must understand, young Hobbit, it takes a long time to say anything in Old Entish. And we never say anything unless it is worth taking a long time to say.

Treebeard: [after seeing the torn-down forest around Isengard] Saruman! A wizard should know better! There is no curse in Elvish, Entish, or the tongues of men for this treachery.

Pippin: Look, the trees! They're moving!

Merry: Where are they going?

Treebeard: They have business with the Orcs. My business is with Isengard tonight, with rock and stone.

[Ents emerge from the woods, following Treebeard]

Treebeard: Hroom, hm, come, my friends. The Ents are going to war. It is likely that we go to our doom. The last march of the Ents.

Gimli: [to a Warg] Bring your pretty face to my axe.

Gandalf: Three hundred lives of men I have walked this earth and now I have no time.

Gandalf: The battle of Helm's Deep is over; the battle for Middle-Earth is about to begin.

The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers (Extended Edition, 2002)

The Lord of the Rings trilogy is one of the most ambitious acts of filmmaking ever attempted - and was pulled off fairly brilliantly by Peter Jackson. While I took the third film in the last draft, this movie fills a different kind of "epic" (226 minute runtime!) film itch - with some of the best battle scenes ever put to film. Emotionally hefty and beautifully filmed, I'm glad to be able to take this with my final pick. One issue I had with the first and third films was the length, as in some parts were dragged out a little longer than they really needed to be. There is much less of that here (except some parts with Gollum). But the films are so well done even that doesn't really detract from the spectacle and experience.

I think the only real issue I had with this film was the whole scene with Aragorn going over a cliff. I mean, what the heck was THAT? It wasn't in the books, and everybody who had ever read the books, which means like 98.4% of the audience, knew that there was literally zero chance that Aragorn dies, seeing as he has to eventually become King and all, so whatever "dramatic tension" it was supposed to build was 100% flaccid. Jackson made 10 good decisions for every bad one, but that particular bad one I've never forgiven.

Quit spoiler-ing an 18-year old trilogy, will ya?I think the only real issue I had with this film was the whole scene with Aragorn going over a cliff. I mean, what the heck was THAT? It wasn't in the books, and everybody who had ever read the books, which means like 98.4% of the audience, knew that there was literally zero chance that Aragorn dies, seeing as he has to eventually become King and all, so whatever "dramatic tension" it was supposed to build was 100% flaccid. Jackson made 10 good decisions for every bad one, but that particular bad one I've never forgiven.

Figures.

This draft was moving at a snail's pace for weeks, and now that I've got stuff to do at work, suddenly the rest of y'all have found time, and now I'm holding y'all up.

Fine, whatever.

I still haven't found time to sit down and work on my write-up for my previous two picks, let alone this one. But, to keep things moving, my final pick in the Shelter-in-Place Movie Draft is:

Harlem Nights (1989)

This draft was moving at a snail's pace for weeks, and now that I've got stuff to do at work, suddenly the rest of y'all have found time, and now I'm holding y'all up.

Fine, whatever.

I still haven't found time to sit down and work on my write-up for my previous two picks, let alone this one. But, to keep things moving, my final pick in the Shelter-in-Place Movie Draft is:

Harlem Nights (1989)

bajaden

Hall of Famer

Quit spoiler-ing an 18-year old trilogy, will ya?Let me guess, next you are going to tell me Darth Vader is Luke Skywalker's dad or something.

Your kidding me! Dam.....

foxfire

G-League

L = The Last Unicorn (1982)

Sticking with Rankin and Bass for the Bonus Bonus Round. This dark favorite is a bit sad for a children's movie, but I love it! The tone is dark, and the danger during the Unicorn's quest is real. Overall, the message in this film is the evolving complexity of adolescence to adulthood, as the innocent/immortal unicorn comes to grips with mortality, it forever changes her perspective.

Link #1 = Trailer

Link #2 = Butterfly

Link #3 = The Red Bull

Link #4 = Ending

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0084237/?ref_=nv_sr_srsg_0

Sticking with Rankin and Bass for the Bonus Bonus Round. This dark favorite is a bit sad for a children's movie, but I love it! The tone is dark, and the danger during the Unicorn's quest is real. Overall, the message in this film is the evolving complexity of adolescence to adulthood, as the innocent/immortal unicorn comes to grips with mortality, it forever changes her perspective.

Link #1 = Trailer

Link #2 = Butterfly

Link #3 = The Red Bull

Link #4 = Ending

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0084237/?ref_=nv_sr_srsg_0

LoungeLizard

Starter

Sticking with the 80s bonus theme....

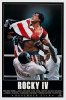

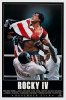

Rocky IV (1985)

This certainly isn’t the most “critically acclaimed” Rocky film but I’ll be damned if it isn’t one of the most entertaining. Some say this movie is what really ended the Cold War

Rocky IV (1985)

This certainly isn’t the most “critically acclaimed” Rocky film but I’ll be damned if it isn’t one of the most entertaining. Some say this movie is what really ended the Cold War

During this fight, I've seen a lot of changing, in the way you feel about me, and in the way I feel about you. In here, there were two guys killing each other, but I guess that's better than twenty million. I guess what I'm trying to say, is that if I can change, and you can change, everybody can change![\QUOTE]

Jespher

Starter

B = Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969) - PG

With a screenplay written by William Goldman (of the Princess Bride fame), and wonderful performances by Paul Neuman, Robert Redford, and Katherine Ross, this Western ranks up there with the best of them!

Link #1 = Knife Fight

Link #2 = Clifftop

Link #3 = Bike Ride

Quotes:

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0064115/?ref_=nv_sr_srsg_0

With a screenplay written by William Goldman (of the Princess Bride fame), and wonderful performances by Paul Neuman, Robert Redford, and Katherine Ross, this Western ranks up there with the best of them!

IMDB - One of the All Time Great Westerns said:One of the best and most-liked films of the 1960s, this is still a fun movie to watch today. When I saw this on DVD on a nice flat-screen set, I was amazed how good this looked. I had seen it several times before on VHS and hadn't realized how good this was photographed. I just discovered Conrad Hall was the cinematographer, which explains it. Few, if any, were better than him.

One remembers this western for several things: the two leads looking over their shoulders incredulous that their pursers seem to be always there; Paul Newman riding a bicycle to the tune of "Raindrops Keep Falling On My Head," the beautiful Katharine Ross, the chemistry of Newman and Robert Redford as a two-man team, on and on. Those three lead actors, with the repartee between them, and the likability of each, make them fun to watch as they dominate this picture.

It's just solid entertainment and another example of good film-making that doesn't need a lot of R-rated material to make it successful. Photography-wise, the western scenery was great, there were some wonderful closeup shots and I really liked the tinted old-time footage inserted in here.

So, when you combine all the elements, it's no surprise this film won so many awards and endures so well.

Link #1 = Knife Fight

Link #2 = Clifftop

Link #3 = Bike Ride

Quotes:

Butch: What happened to the old bank? It was beautiful.

Guard: People kept robbing it.

Butch: Small price to pay for beauty.

Macon: I didn't know you were the Sundance Kid when I said you were cheating. If I draw on you, you'll kill me.

Sundance: There's that possibility.

Butch: No, you'd be killin' yourself. So why don't you just invite us to stick around? You can do it, and easy. Come on. Come on.

Macon: [stiffly] Why don't you stick around?

Butch: Thanks but, hah, we gotta get goin'. [He scoops up the Kid's winnings into his hat]

Macon: Hey Kid! Hey Kid! How good are ya?[Sundance dives, whirls around, fans his gun and fires, demonstrating his lightning-fast draw. He detaches the gunman's gunbelt from his waist and sends his gun skittering and spiraling across the floor]

Butch: [to Sundance as they both leave] Like I've been tellin' ya, over the hill.

Butch: Boy, y'know, every time I see 'Hole in the Wall' again, it's like seeing it fresh for the first time, and every time that happens, I keep asking myself the same question, 'How can I be so damn stupid as to keep comin' back here?'

Harvey: Guns or knives?

Butch: Neither.

Harvey: Pick!

Butch: I don't wanna shoot with ya, Harvey.

Harvey: [pulling out a large Bowie knife] Anything you say, Butch.

Butch: [low voice, to Sundance] Maybe there's a way to make a profit in this. Bet on Logan.

Sundance: I would, but who'd bet on you?'

Harvey: Sundance, when we're done and he's dead, you're welcome to stay.

Butch: [low voice, to Sundance] Listen, I don't mean to be a sore loser, but when it's done, if I'm dead, kill him.

Sundance Kid: [low voice to Butch] Love to.[waves to Harvey and smiles]

Butch: No, no, not yet, not until me and Harvey get the rules straightened out.

Harvey: Rules? In a knife fight? No rules! [Butch kicks Harvey in the groin]

Butch: Well, if there aint' going to be any rules, let's get the fight started. Someone count. 1,2,3 go.

Sundance: 1,2,3, go! '['Butch knocks Harvey out]

Flat Nose: I was really rooting for you, Butch.

Butch: Well, thank you, Flatnose. That's what sustained me in my time of trouble.

Butch: (singing) Don't ever hit your mother with a hammer, it leaves a dull impression on her mind.

Butch: Do you believe I'm broke already?

Etta: Why is there never any money, Butch?

Butch: Well, I swear, Etta, I don't know. I've been working like a dog all my life and I can't get a penny ahead.

Etta: Sundance says it's because you're a soft touch, and always taking expensive vacations, and buying drinks for everyone, and you're a rotten gambler.

Butch: Well that might have something to do with it.

Butch: Well, the way I figure it, we can either fight or give. If we give, we go to jail.

Sundance: I've been there already.

Butch: We could fight - they'll stay right where they are and starve us out. Or go for position, shoot us. Might even get a rock slide started, get us that way. What else can they do?

Sundance: They could surrender to us, but I wouldn't count on that. They're goin' for position, all right. Better get ready. [He loads his gun]

Butch: Kid - the next time I say, 'Let's go someplace like Bolivia,' let's go someplace like Bolivia.

Sundance: Next time. Ready?

Butch: [looking into the deep canyon and the river far below] No, we'll jump.

Sundance: Like hell we will.

Butch: No, it'll be OK - if the water's deep enough, we don't get squished to death. They'll never follow us.

Sundance: How do you know?

Butch: Would you jump if you didn't have to?

Sundance: I have to and I'm not gonna.

Butch: I'll jump first.

Sundance: Nope.

Butch: Then you jump first.

Sundance: No, I said!

Butch: What's the matter with you?!

Sundance: I can't swim!

Butch: [laughing] Why, you crazy — the fall'll probably kill ya!

Sundance: [to Etta] What I'm saying is, if you want to go, I won't stop you. But the minute you start to whine or make a nuisance, I don't care where we are, I'm dumping you flat.

Butch: Don't sugarcoat it like that, Kid. Tell her straight.

Etta: I'm 26, and I'm single, and a school teacher, and that's the bottom of the pit. And the only excitement I've known is here with me now. I'll go with you, and I won't whine, and I'll sew your socks, and I'll stitch you when you're wounded, and I'll do anything you ask of me except one thing. I won't watch you die. I'll miss that scene if you don't mind.

Butch: Kid, there's somethin' I think I oughta tell ya. I never shot anybody before.

Sundance: One hell of a time to tell me!

Butch: Is that what you call giving cover?

Sundance: Is that what you call running? If I knew you were gonna stroll...

Butch: You never could shoot, not from the very beginning.

Sundance: And you were all mouth.

Guard: People kept robbing it.

Butch: Small price to pay for beauty.

Macon: I didn't know you were the Sundance Kid when I said you were cheating. If I draw on you, you'll kill me.

Sundance: There's that possibility.

Butch: No, you'd be killin' yourself. So why don't you just invite us to stick around? You can do it, and easy. Come on. Come on.

Macon: [stiffly] Why don't you stick around?

Butch: Thanks but, hah, we gotta get goin'. [He scoops up the Kid's winnings into his hat]

Macon: Hey Kid! Hey Kid! How good are ya?[Sundance dives, whirls around, fans his gun and fires, demonstrating his lightning-fast draw. He detaches the gunman's gunbelt from his waist and sends his gun skittering and spiraling across the floor]

Butch: [to Sundance as they both leave] Like I've been tellin' ya, over the hill.

Butch: Boy, y'know, every time I see 'Hole in the Wall' again, it's like seeing it fresh for the first time, and every time that happens, I keep asking myself the same question, 'How can I be so damn stupid as to keep comin' back here?'

Harvey: Guns or knives?

Butch: Neither.

Harvey: Pick!

Butch: I don't wanna shoot with ya, Harvey.

Harvey: [pulling out a large Bowie knife] Anything you say, Butch.

Butch: [low voice, to Sundance] Maybe there's a way to make a profit in this. Bet on Logan.

Sundance: I would, but who'd bet on you?'

Harvey: Sundance, when we're done and he's dead, you're welcome to stay.

Butch: [low voice, to Sundance] Listen, I don't mean to be a sore loser, but when it's done, if I'm dead, kill him.

Sundance Kid: [low voice to Butch] Love to.[waves to Harvey and smiles]

Butch: No, no, not yet, not until me and Harvey get the rules straightened out.

Harvey: Rules? In a knife fight? No rules! [Butch kicks Harvey in the groin]

Butch: Well, if there aint' going to be any rules, let's get the fight started. Someone count. 1,2,3 go.

Sundance: 1,2,3, go! '['Butch knocks Harvey out]

Flat Nose: I was really rooting for you, Butch.

Butch: Well, thank you, Flatnose. That's what sustained me in my time of trouble.

Butch: (singing) Don't ever hit your mother with a hammer, it leaves a dull impression on her mind.

Butch: Do you believe I'm broke already?

Etta: Why is there never any money, Butch?

Butch: Well, I swear, Etta, I don't know. I've been working like a dog all my life and I can't get a penny ahead.

Etta: Sundance says it's because you're a soft touch, and always taking expensive vacations, and buying drinks for everyone, and you're a rotten gambler.

Butch: Well that might have something to do with it.

Butch: Well, the way I figure it, we can either fight or give. If we give, we go to jail.

Sundance: I've been there already.

Butch: We could fight - they'll stay right where they are and starve us out. Or go for position, shoot us. Might even get a rock slide started, get us that way. What else can they do?

Sundance: They could surrender to us, but I wouldn't count on that. They're goin' for position, all right. Better get ready. [He loads his gun]

Butch: Kid - the next time I say, 'Let's go someplace like Bolivia,' let's go someplace like Bolivia.

Sundance: Next time. Ready?

Butch: [looking into the deep canyon and the river far below] No, we'll jump.

Sundance: Like hell we will.

Butch: No, it'll be OK - if the water's deep enough, we don't get squished to death. They'll never follow us.

Sundance: How do you know?

Butch: Would you jump if you didn't have to?

Sundance: I have to and I'm not gonna.

Butch: I'll jump first.

Sundance: Nope.

Butch: Then you jump first.

Sundance: No, I said!

Butch: What's the matter with you?!

Sundance: I can't swim!

Butch: [laughing] Why, you crazy — the fall'll probably kill ya!

Sundance: [to Etta] What I'm saying is, if you want to go, I won't stop you. But the minute you start to whine or make a nuisance, I don't care where we are, I'm dumping you flat.

Butch: Don't sugarcoat it like that, Kid. Tell her straight.

Etta: I'm 26, and I'm single, and a school teacher, and that's the bottom of the pit. And the only excitement I've known is here with me now. I'll go with you, and I won't whine, and I'll sew your socks, and I'll stitch you when you're wounded, and I'll do anything you ask of me except one thing. I won't watch you die. I'll miss that scene if you don't mind.

Butch: Kid, there's somethin' I think I oughta tell ya. I never shot anybody before.

Sundance: One hell of a time to tell me!

Butch: Is that what you call giving cover?

Sundance: Is that what you call running? If I knew you were gonna stroll...

Butch: You never could shoot, not from the very beginning.

Sundance: And you were all mouth.

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0064115/?ref_=nv_sr_srsg_0

Last edited:

bajaden

Hall of Famer

G = The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo: Based on a novel of the same name by Stieg Larsson, and having previously been made into a movie in Sweden, this version was a big box office success It was directed by David Fincher and starred Daniel Craig, of James Bond fame and with Rooney Mara in the title role. Mara earned an academy award nomination for best actress for her efforts. It has a stellar supporting cast made up of Stellan Skarsgard, Christopher Plummer and Robin Wright. Having read the book (actually I've read the entire series), I can attest that the movie stayed fairly true to the book.

In Stockholm, disgraced journalist Mikael Blomkvist (Craig) is recovering from the legal and professional fallout of a libel suit brought against him by businessman Hans-Erik Wennerström, straining Blomkvist's relationship with his business partner and married lover, Erika Berger. Lisbeth Salander (Mara), a young, brilliant but antisocial investigator and hacker, compiles an extensive background check on Blomkvist for the wealthy Henrik Vanger (Plummer), who offers Blomkvist evidence against Wennerström in exchange for an unusual task: investigate the 40-year-old disappearance and presumed murder of Henrik's grandniece, Harriet. Blomkvist agrees, and moves into a cottage on the Vanger family estate on Hedestad Island.

Salander's state-appointed guardian, Holger Palmgren, suffers a stroke and is replaced by Nils Bjurman, a sadist who controls Salander's finances and extorts sexual favors by threatening to have her institutionalized. Unaware she is secretly recording one of their meetings, Bjurman brutally rapes her.

This is a suspenseful movie that leads you in one direction and then takes you in a different one. It's full of little surprises you won't see coming.

In Stockholm, disgraced journalist Mikael Blomkvist (Craig) is recovering from the legal and professional fallout of a libel suit brought against him by businessman Hans-Erik Wennerström, straining Blomkvist's relationship with his business partner and married lover, Erika Berger. Lisbeth Salander (Mara), a young, brilliant but antisocial investigator and hacker, compiles an extensive background check on Blomkvist for the wealthy Henrik Vanger (Plummer), who offers Blomkvist evidence against Wennerström in exchange for an unusual task: investigate the 40-year-old disappearance and presumed murder of Henrik's grandniece, Harriet. Blomkvist agrees, and moves into a cottage on the Vanger family estate on Hedestad Island.

Salander's state-appointed guardian, Holger Palmgren, suffers a stroke and is replaced by Nils Bjurman, a sadist who controls Salander's finances and extorts sexual favors by threatening to have her institutionalized. Unaware she is secretly recording one of their meetings, Bjurman brutally rapes her.

This is a suspenseful movie that leads you in one direction and then takes you in a different one. It's full of little surprises you won't see coming.

Jespher

Starter

Here is a list of some alternates I had:

American History X

Cloud Atlas

The God’s Must Be Crazy

He Got Game

How the West Was Won

The Illusionist

Ladyhawke

Last of the Mohicans

Limitless

Magnolia

Mary Poppins

Maverick

The Nightmare Before Christmas

Rain Man

Rounders

Reservoir Dogs

Seven Pounds

Silver Lining’s Playbook

Six Days, Seven Nights

Skyfall

The Sound of Music

Star Trek

There’s Something About Mary

The Time Traveler’s Wife

To Kill a Mockingbird

True Romance

American History X

Cloud Atlas

The God’s Must Be Crazy

He Got Game

How the West Was Won

The Illusionist

Ladyhawke

Last of the Mohicans

Limitless

Magnolia

Mary Poppins

Maverick

The Nightmare Before Christmas

Rain Man

Rounders

Reservoir Dogs

Seven Pounds

Silver Lining’s Playbook

Six Days, Seven Nights

Skyfall

The Sound of Music

Star Trek

There’s Something About Mary

The Time Traveler’s Wife

To Kill a Mockingbird

True Romance

A few comments:

There are a few other movies I like that aren't necessarily well thought of. Some I wanted to take but never worked them in. Some I just like and didn't think they were worth adding to the list, but they are fun/interesting for various reasons.

Demolition Man (1993) was always enjoyable (with Sandra Bullock and Sly Stallone and Denis Leary, but I think suffers most from Wesley Snipes overplaying his role a bit).

I like Ender's Game (2013) just because that is one of my favorite books of all time (the roles of Andrew "Ender" Wiggin and some of the children were played a bit too stiffly for my taste, but Harrison Ford and Ben Kingsley did well). The special effects were very well done, and I like the visualization of the final battle with the Formics.

I kinda wanted to grab Forbidden Planet (1956) just because it was one of my dad's favorite early sci-fi flicks and they had cool creature effects for the time (not shown in the trailer!). Also, a VERY young Leslie Nielsen.

I like Mr. & Mrs. Smith (2005) WAY more than I should for the quick humor and chemistry between Jolie and Pitt and Vince Vaughn.

When I said I watched A Few Good Men and it really reminded me of a movie five years prior, it was From the Hip (1987, Judd Nelson and John Hurt). A young wiseacre attorney that wants to try a case, gets a major murder case assigned to him, thinks that the defendant actually did it, and tries to figure out a way to get him to confess on the stand. Not a "great" movie, and fairly poorly reviewed, but I enjoyed it when I saw it on video about 30 years ago. Had some pretty funny/clever stuff mixed in there, especially the part where he parlayed a no-win 1-day assault case into a several-day first amendment argument before the judge.Just watched this for the first time the other day.

And it struck me in how many ways it was similar it was to another movie (I can't name yet) that came out 5 years before this one. As in, to a large extent, almost identical with the major themes/plot points.

There are a few other movies I like that aren't necessarily well thought of. Some I wanted to take but never worked them in. Some I just like and didn't think they were worth adding to the list, but they are fun/interesting for various reasons.

Demolition Man (1993) was always enjoyable (with Sandra Bullock and Sly Stallone and Denis Leary, but I think suffers most from Wesley Snipes overplaying his role a bit).

I like Ender's Game (2013) just because that is one of my favorite books of all time (the roles of Andrew "Ender" Wiggin and some of the children were played a bit too stiffly for my taste, but Harrison Ford and Ben Kingsley did well). The special effects were very well done, and I like the visualization of the final battle with the Formics.

I kinda wanted to grab Forbidden Planet (1956) just because it was one of my dad's favorite early sci-fi flicks and they had cool creature effects for the time (not shown in the trailer!). Also, a VERY young Leslie Nielsen.

I like Mr. & Mrs. Smith (2005) WAY more than I should for the quick humor and chemistry between Jolie and Pitt and Vince Vaughn.

My wife and I like to throw in The Peacemaker (1997) every once in a while (Kidman and Clooney).

I want to like Ready Player One (2018) more as the book was awesome, but they removed all the cool D&D references and a lot of the other '80's stuff (especially Spielberg's, who directed it and demanded that his own stuff not be in there). That sucked out a lot of the references that made the book so fun to read for someone who grew up in the 80's(±)!

The Ref (1994) is a funny little movie with Kevin Spacey and Denis Leary.

I debated picking Spaceballs (1987) just for some more stupid humor.

The Shape of Water (2017, by Guillermo del Toro) was another VERY well done movie I really was trying to convince myself to fit in there.

I want to like Ready Player One (2018) more as the book was awesome, but they removed all the cool D&D references and a lot of the other '80's stuff (especially Spielberg's, who directed it and demanded that his own stuff not be in there). That sucked out a lot of the references that made the book so fun to read for someone who grew up in the 80's(±)!

The Ref (1994) is a funny little movie with Kevin Spacey and Denis Leary.

I debated picking Spaceballs (1987) just for some more stupid humor.

The Shape of Water (2017, by Guillermo del Toro) was another VERY well done movie I really was trying to convince myself to fit in there.

Seeing as this thread has been dormant for a bit, I'll chime in with a few of the films that just didn't make the cut for me:

Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead: A quirky take on Hamlet from the POV of two minor characters. With Gary Oldman and Tim Roth in the leading roles it's an instant winner. But I knocked out my "R" pick real quick and my "relaxed Z" pick got stolen by The Wizard of Oz, so RnGrD lost out.

Moon: Directed by Duncan Jones, a name that means nothing to people until they realize that a budding English musician named David Jones got beaten to the punch by the lead singer of The Monkees ("Davey Jones") and changed his stage name to: David Bowie. Duncan Jones is Bowie's son. And Moon packs more punch per lame title than any movie ever, starring Sam Rockwell and Sam Rockwell and the voicework of Kevin Spacey. It's a movie with a twist, but instead of revealing it at the end it reveals it fairly early and the main plot of the film is dealing with the twist. A great movie, but I hit so many sci-fi films I couldn't justify taking another.

Donnie Darko: If you've seen it, you get it. If you haven't seen it, watch this movie. Twice. It won't make sense the first time. This film is incredibly complicated, a tightly-scripted tangent universe sci-fi journey about a high-school kid coming to grips with an ugly fate and probably saving the space-time continuum in the process. In all honesty, this film deserves more re-watches than any movie I picked just to finally figure out what the heck is going on. If you want to explain this film, you need a dissertation, not an essay. But again, my sci-fi docket was so full (and Dr. Strangelove called so softly) that I had to let it go.

Silence: Everybody thinks Martin Scorsese is brilliant, because he is. But while he's largely known for gangster films, several of his non-gangster films really stand out to me. "The Last Temptation Of Christ" - also a shortlisted film - was one for me. But perhaps more than any, Silence touched me in a way few films do. Unlike the previous two films on my list it's not a complicated story: in the 17th-century Edo era of Japan, when Christianity was outlawed, two Portuguese Jesuit priests nonetheless sneak onto the mainland of Japan to preach their gospel, and run afoul of the authorities. It's amazing that a man best known for the shoot-em-up has produced not one but two of the most deeply spiritual films around, but Scorsese has in fact done so.

Se7en: Why didn't anybody take this? I have a love-hate relationship with Brad Pitt - I can't decide whether he's terrible or a damned genius - and the end of this movie is the epitome of my conundrum. "What's in the box?" he whines. "What's in the m-er-f-ing box?!?" And if you've seen it, you'll never, ever forget it.

That's five. There were more, but that's five for you.

Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead: A quirky take on Hamlet from the POV of two minor characters. With Gary Oldman and Tim Roth in the leading roles it's an instant winner. But I knocked out my "R" pick real quick and my "relaxed Z" pick got stolen by The Wizard of Oz, so RnGrD lost out.

Moon: Directed by Duncan Jones, a name that means nothing to people until they realize that a budding English musician named David Jones got beaten to the punch by the lead singer of The Monkees ("Davey Jones") and changed his stage name to: David Bowie. Duncan Jones is Bowie's son. And Moon packs more punch per lame title than any movie ever, starring Sam Rockwell and Sam Rockwell and the voicework of Kevin Spacey. It's a movie with a twist, but instead of revealing it at the end it reveals it fairly early and the main plot of the film is dealing with the twist. A great movie, but I hit so many sci-fi films I couldn't justify taking another.

Donnie Darko: If you've seen it, you get it. If you haven't seen it, watch this movie. Twice. It won't make sense the first time. This film is incredibly complicated, a tightly-scripted tangent universe sci-fi journey about a high-school kid coming to grips with an ugly fate and probably saving the space-time continuum in the process. In all honesty, this film deserves more re-watches than any movie I picked just to finally figure out what the heck is going on. If you want to explain this film, you need a dissertation, not an essay. But again, my sci-fi docket was so full (and Dr. Strangelove called so softly) that I had to let it go.

Silence: Everybody thinks Martin Scorsese is brilliant, because he is. But while he's largely known for gangster films, several of his non-gangster films really stand out to me. "The Last Temptation Of Christ" - also a shortlisted film - was one for me. But perhaps more than any, Silence touched me in a way few films do. Unlike the previous two films on my list it's not a complicated story: in the 17th-century Edo era of Japan, when Christianity was outlawed, two Portuguese Jesuit priests nonetheless sneak onto the mainland of Japan to preach their gospel, and run afoul of the authorities. It's amazing that a man best known for the shoot-em-up has produced not one but two of the most deeply spiritual films around, but Scorsese has in fact done so.

Se7en: Why didn't anybody take this? I have a love-hate relationship with Brad Pitt - I can't decide whether he's terrible or a damned genius - and the end of this movie is the epitome of my conundrum. "What's in the box?" he whines. "What's in the m-er-f-ing box?!?" And if you've seen it, you'll never, ever forget it.

That's five. There were more, but that's five for you.

Löwenherz

Starter

I know, I know; way late getting back to this, and pretty sure everyone's moved on by now (other than Cap apparently). But things have finally quieted to a gentle, containable roar following the first two weeks of navigating distance learning, and I'd like to drudge this thread back up to close things out per tradition.

Also, hoping Slim finds his way back for what I expect to be a razor sharp and mindbogglingly ocean's deep dissertation on Black Panther.

Gonna put a bow on this with a series of themed Top Ten lists.

Oh, one quick note first though; Apocalypse Now ladies and gentlemen. Killed me to watch my favorite movie free fall for 30 rounds. Debate raged in my head whether to let it go, or break my own rule and nab it just so I could gush about it for the third time. Big reason "A" was the last letter I took, aside from Amelie being stolen out from under me early.

Speaking of which,

Top Ten Movies I Wanted / Others Took

Blade Runner (1982)

I didn't see Blade Runner for the first time until a full 30 years after its initial release, and I still gasped out loud, mouth fully agape, eyes fixed as Zhora crashed through neon-lit windows and a flurry of fake snow, muttering in a stunned monotone: "This is the coolest movie I have ever seen." No one else was in the room to hear it, but it felt vital to give voice to that epiphany in the moment. (You may note a theme, whenever I call a movie "cool" or indeed "the coolest movie I've ever seen" while still in the act of actively watching it for the first time, it's automaticlly earned a place in my upper echelons.)

After three straight whiffs, I needed to take Back to the Future this time around (Just as much as @Padrino needed to take Blade Runner), so I was never really in the running given the alphabet rules. But as far as these games are concerned, Blade Runner (Final Cut) most assuredly has become my new draft game unicorn.

Did ... did you see what I did there? Padrino knows.

Blade Runner 2049 (2017)

Thanks to my late arrival to the fandom, I only had 5 years to wait for the impossible-to-predict, and seemingly unnecessary sequel. Still I was beyond hyped. I don't remember when or where I first got the news of 2049, but I distinctly remember my reaction being a gleeful "Ohmygod, ohmygod, ohmygod." That was quickly crushed by my own disciplined, swift and sobering cynicism pigeonholing it as yet another 18-to-35 target demo resurrected-from-childhood legacy IP cash-grab. It took a series of leaks turning into floods of slick trailers and gushing reviews to build back my giddy optimism.

Yeah, to put it plainly, this one is an impossibly monumental achievement. It naturally builds and expands on the narrative, mythos, and universe of the first film, while keeping the essence and mysteries intact. It is simultaneously its own self-contained film, and a perfectly balanced part of a whole. Watching 2049 is like finding the companion piece to a breathtaking painting you had no idea was a part of a set. Plus, it’s stunningly gorgeous, as we've come to expect from Deakins and Villeneuve.

There are a few parts that irk me ever-so-slightly (The scene with the one-eyed replicant sewer resistance leader could have been a little more creatively intimate and mysterious, rather than a straight exposition dump in a kinda dark hallway), and even as one who loves a cerebral slow-burner, I find portions drag, but overall I am just in awe that this film exists, and can be ranked among the best sequels ever made.

2017 was a busy year for me: I got married, earned my teaching credential, and still worked full-time for San Diego EMS. I only made it to the theater for one movie that whole year. 2049 was my lone choice. And I wouldn't change a thing.

Amelie (2001)

This got upgraded from my "leftover" afterthought list last time, to the top tier of titles that hurt the most when it was straight up stolen a round before I got to it. That one burned.