We wanted to show violence in real terms. Dying is not fun and games. Movies make it look so detached. With ‘The Wild Bunch,’ people get involved whether they like it or not. They do not have the mild reactions to it. When we were actually shooting, we were all repulsed at times. There were nights when we’d finish shooting and I’d say, “My God, my God!” But I was always back the next morning, becasue I sincerely believed we were achieving something. […] To tell you the truth, I really cannot stand to see the film myself anymore. It is too much an emotional thing. I saw it last night, but I do not want to see it again for perhaps five years. —Sam Peckinpah

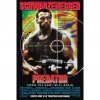

Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch is the film alliterative praise was made for: bold, balletic, ballistic, and bloodily beautiful. If Sir Christopher Frayling described Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in the West as “something to do with death” then add “life” to that imprimatur and slap it on Bloody Sam’s magnum opus. His outlaw “heroes” embody all his favorite themes: comradeship, independence, betrayal. Also a love for Mexico and its sultry passions, with a feeling of the times leaving these men and their ways behind—all culminating in a final, defiant raging against the dying of the light. The basis of the story began as a pitch from Hollywood stunt performer, “Marlboro Man,” and bit part actor Roy N. Sickner, looking to power move up the chain to producer of his own material. He also came up with the title. In 1964, he doubled for Richard Harris on Sam Peckinpah’s Major Dundee, an attempt to do a gritty, sprawling obsessive horse soldier quest loosely in the vein of Moby Dick and aiming for the scope of Lawrence of Arabia, which foundered on the mantle of an incomplete script, Peckinpah’s own fiery temperament and drinking, and difficult, sprawling Mexican locations. Taken from him and cavalry sabred into a shadow of what it was, it has in recent years been recut into something approximating his original intent. It remains a fascinating, flawed film, where Peckinpah’s themes and obsessions began to evolve. It was here Sickner first pitched the idea for The Wild Bunch to Peckinpah. It would take several years for him to regain enough favor with the suits of Hollywood to pursue the project, determined not to make the same mistakes as on Dundee. He honed the script for years, continuing to work on it with Sickner’s development partner Walon Green, a young screenwriter and student of Mexican culture, who had persuaded Sickner to set the story later than originally intended, along the Texas/Mexico border during the Mexican Revolution of the 1910s.

It is now 1913: Pike Bishop (William Holden) and his gang have ended up in Mexico after a failed and bloody Railroad office robbery in the town of Starbuck on the US side of the Texas/Mexico border, and have fallen in with the corrupt General Mapache (Emilio Fernandez). Lee Marvin was originally approached by Green and Sickner to play Bishop, and he was enthusiastic, with a lot of his own ideas. It was his suggestion for the gang at the beginning of the film to enter Starbuck in disguise. “Since you’re setting it in a different era from most westerns, why don’t you really go there? Why don’t you have these guys come into town looking like Pershing’s troops along the border, you know, dressed as doughboys?” It made perfect sense given the dangerous tensions along the border at the time. Marvin’s agent Meyer Mishkin was never keen on his star appearing in such a nihilistic western though, and instead set him up with a major payday deal of $1 million to appear with Clint Eastwood in the big-screen adaptation of Lerner and Loewe’s Broadway musical Paint Your Wagon. Truth be told, Marvin was beginning to cool on the idea, feeling his turn in the similarly themed Mexican revolution western The Professionals, followed by this, would typecast him. William Holden was an inspired substitute, the role of Pike Bishop allowing the fading star to deliver a multi-layered performance, by turns remorseful, clever, foolish, haunted, bitter, loyal, angry, desperate, but always in charge.

Pike, Ernest Borgnine as Dutch Engstrom, his loyal lieutenant, and Deke Thornton (Robert Ryan), Pike’s former partner he left behind to be captured and corralled by the venal railroad boss Harrigan (Albert Dekker) into hunting down Pike and the gang with a bunch of oddball bounty hunting scum in return for staying out of jail, comprise a sort of bromantic love triangle. Deke and his cohorts are staked out in Starbuck with Harrigan to ambush the Wild Bunch, but his hopeless amateurs give the game away, leading to a bloody shoot-out where innocent men and women (many temperance Bible-thumpers) are mown down in the melee. Deke and Pike lock eyes, but Deke hesitates to fire, and a tuba player gets gunned down crossing Pike’s path instead. Asked at an angry press conference during the film’s publicity trail why he hadn’t gone the whole hog and shown any children being blown away, Peckinpah replied, “Because I’m constitutionally unable to show a child in jeopardy.” He instead used children to bookend the opening slaughter by laughing as they pit scorpions against ants before covering them with straw and burning them. There are no innocents in this world, he says. Holden was irritated with the line of questioning. “I just can’t get over the reaction here. Are people surprised that violence really exists in the world? Just turn on your TV set any night. The viewer sees the Vietnam war, cities burning, campus riots. He sees plenty of violence.” Roger Ebert stepped up to defend the film to the stars and director. “I suppose all of you up there are getting the impression that this film has no defenders. That’s not true. A lot of us think The Wild Bunch is a great film. It’s hard to ask questions about a film you like, easy about one you hate. I just wanted it said: to a lot of people, this film is a masterpiece.”

A lot of the credit for it being considered a masterpiece comes down to the confluence of myriad elements coming together beautifully—Lucien Ballard’s cinematography, by turns dusty and dirty, then greenly idyllic in Angel’s village (ironically, Ballard believed that “I prefer working where I can control things, and you can’t outdoors.”); Jerry Fielding’s brilliant score and sourcing of authentic Mexican folk music; Lou Lombardo’s genius editing; and the brilliant use of multi-camera set-ups and slow-motion slaughter. It’s all there in the opening ambush (just check out the slow-motion firefight homage in a western town in Walter Hill’s The Long Riders) but the glorious, bloody, cynical finale is a thing to behold. For delivering a crate of U.S army guns to their compatriot Angel’s rebel villagers in lieu of delivering them with the full stolen consignment to Mapache, Angel (Jaime Sánchez) is captured and badly beaten. This is also partly in revenge for Angel having previously shot a former lover, now in Mapache’s favors, in jealousy. The gang have their opportunity to leave Mapache’s Agua Verde compound during a bawdy fiesta, but Pike decides no: earlier, he’d stated “When you side with a man, you stay with him, and if you can’t do that you’re like some animal (conveniently forgetting they hightailed it out of Starbuck without Bo Hopkins’ “Crazy” Lee, forgotten and guarding their hostages).” What follows is the most incredible climax, a lot of the surrounding color and shading largely improvised.

The scene comprises a scant few lines in the script, belying the detail and mayhem Peckinpah put on screen. Pike pays off a sleepy young prostitute, the camera and his eyes lingering on her restless infant, soft Mexican music lilting over the soon to be shattered peace. The mood is funereal, not festive. He takes up his shotgun, locating Tector Gorch (Ben Johnson), and his brother Lyle Gorch (Warren Oates). “Let’s go,” he simply says. “Why not?” replies Tector. Peckinpah’s co-writer Walon Green says of the minimalist, terse exchange: “If the movie doesn’t say it, there’s no line in the world that’s gonna help.” Author W.K. Stratton, in his book, The Wild Bunch: Sam Peckinpah, a Revolution in Hollywood, and the Making of a Legendary Film, states, “With that, a cloud lifts. Their former lives are finished, fading away like the dying bird on a string that Tector Gorch has been toying with.”

They walk off, adding Dutch to their number, who feels guilty for abandoning Angel earlier to Mapache’s men (Peckinpah deliberately framed the young Mexican’s torment at the hands of the soldiers as a Jesus parallel, Dutch abandoning him in a Gethsemane moment as a cross between the denial of Saint Peter and the betrayal of Judas). Pike’s right hand reads his friend’s expression without the need for words of intent. The bunch stride line abreast, guns cradled in crooks of arms through the dozing, drunken villagers, playing children and curious soldiers, until they arrive at Mapache’s post—bacchanalian courtyard, and demand Angel in front of hundreds of groggy, curious Federales. An insistent, determined rising drumbeat matches their steps, a counter-melody to the diegetic Mexican sing-off. This dramatic “walk thing” was improvised by Peckinpah on the spot. Quickly the walk was choreographed through the foreground and background onlookers—D.P. Lucien Ballard used a telephoto lens to keep everything in focus. This expensive lens had been sitting unused until now. Panavision wanted it back. A day before it was to be returned, it finally came into its own. At one point the bunch step through a collapsed section of wall, “the opening resembling nothing so much as a vagina. The symbolism is clear: They have been reborn.” —W.K. Stratton.

The Wild Bunch: An Album in Montage, a 32-minute documentary by Paul Seydor and Nick Redman, comprised on-set footage of the finale discovered in 16mm canisters in the Warner Brothers vaults in 1995. “Whoever it was behind the camera,” acknowledges Seydor, “picked the right three days to shoot. And it’s all so loose and spontaneous; almost as if Peckinpah and the crew were unaware they were being filmed. I’ve theorized that the shooter was a member of the camera crew. The camera on which it was shot was a handheld Bolex, with a wind-up motor. They were essentially like the video cameras of today; people just shot them the way they take snapshots.”

When Mapache seems to agree to Angel’s release, then relents and slits his throat, Pike bellows his outrage and blows a hole in him with an automatic, foregoing his old-world six-shooter, Dutch adding a shotgun blast. Everyone freezes; time stands still. They could back off, but something electric in the air tells them this is it. Dutch’s darting eyes glitter; he giggles. Lyle catches his eye and laughs too. Then Pike shoots the German army advisor to Mapache, symbol of the hated unfeeling industrialization of the new world, and hell opens up on earth, hundreds of Mexican soldiers mown down by rifle, handgun, grenades, and the General’s prized machinegun; the wild bunch shot to pieces themselves.

This whole climactic shoot-out, known as The Battle of Bloody Porch, took 12 days to film. It comprised 325 edits in around five minutes of screen time. Multiple cameras shot simultaneously at different speeds, from 24 frames per second to 120, the frames spliced together later to make it appear as if time itself is elastic—we are experiencing the curious sensation of being in the melee, where time can appear to speed up, coalesce into a diamond-sharp moment of clarity, or slow to a crawl, while bullets fly and explosions shake the senses. An effect Peckinpah had hoped to use in his earlier, Civil War period Mexican incursion, Major Dundee–an homage to Akira Kurasawa’s Seven Samurai.

Costumer Gordon Dawson had 350 or so Mexican army uniforms—many more of Mapache’s men fall than that. Extras costumes would be patched up, khaki paint covering those patches to match the uniform, heater lamps constantly drying off washed blood squib stains. The squibs (10,000!) were loaded with blood and raw meat, bloodstains painted black because, as Peckinpah said, “blood blackens as it dries.” Dawson recalled that:

“Five or six cameras side by side, shooting the whole master shot, with various lenses, but shooting the whole thing. And moving the entire setup five feet. And then shooting it all again. And then moving it five feet, and shooting it all again… All the blood hits on the wall had to be cleaned up every time. All those people who just ran in and got shot, now we’re going to shoot it again, and they’re going to get shot again. They’ve got to come back in, in clean clothes. I don’t know. It was like five or six days this way. And then they say, ‘OK, boys, turn it around, we’re going back the other way.’”

Dutch earlier appears to be the conscience of the group. During the Starbuck debacle, before the chaos, he bumps into an old woman and courteously retrieves her spilled packages, offering his arm to escort her across the road—although she later dies in the melee, trampled underfoot as well by stampeding horses. He scolds Pike for saying they and Mapache aren’t so different. “We ain’t nothin’ like him! We don’t hang nobody! I hope someday these people here kick him and the rest of that scum like him, right into their graves.” Now though Dutch grabs a woman as a human shield without a second thought; Pike shoots a young woman who shoots him in the back (“*****!”); a boy soldier finishes him off. A bullet-riddled Dutch crawls to die by his side. The Mexican stand-off can end only one way. Peckinpah said:

“I was trying to tell a simple story about bad men in changing times. The Wild Bunch is simply about what happens when killers go to Mexico. The strange thing is that you feel a great sense of loss when these killers reach the end of the line.” None more so than Deke Thornton, who at last feels his onerous task is done. As his odd bunch compete with the buzzards over the pickings, he tenderly retrieves Pike’s unused six-shooter from its holster in tribute to his fallen erstwhile colleague. The Wild Bunch’s elderly compatriot Freddie Sykes (Edmond O’Brien) turns up with Angel’s fellow villagers, now armed and ready to join Pancho Villa in the revolutionary struggle, offering a place for Deke in their number. O’Brien’s copy of the script has two pivotal lines of his annotated in green ink that were not there originally. Whether he came up with them himself or they arose organically through rehearsals, the second in particular summed up the spirit of not just the story, but the film itself, and the seismic change it represented: “It ain’t like it used to be. But it’ll do.”