I've been doing PA at my son's school for the sports he plays and I think I am ready to take on basketball if they will have me. Volleyball I very much used "arcade voice" (a little bit of SF II announcer) when calling points. So much fun and I will totally go NBA Jam style if they let me.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The 2025 Desert Island Video Game Draft

- Thread starter Capt. Factorial

- Start date

Insomniacal Fan

Starter

Ebert's conclusion (the headline) was paired with a weaker argument than his own, that's a strawman. The article you linked is a rebuttal; to a criticism; of his argument, it doesn't actually contain his original point of view. One ought to work a bit to understand someone's point of view in order to refute it. Don't dig up someone's grave just to take a crap in it.I think if you read the full extent of my argument, I did address Ebert's main criticism. I think all games are capable of being art not by becoming more like cinema (a linear format where the author presents a finished work to the viewer) but by remaining true to their origins as interactive media. I love cinema for what it is but Roger Ebert was quite simply a snob. Not a big deal, so am I and I'm sure we both have some redeeming qualities.

I also don't think I'm straw-manning the guy when he chose to call his essay "Video Games Can Never Be Art". He was a newspaper columnist so it's possible he didn't write the headline himself, but nonetheless it's archived on his website and he allowed it to be called that so I think it's fair to hold him to account for his own bold thesis.

Here's what he wrote in 2012:

I think he's already wrong. And that's not because I'm intending to convince you that there is one game we all can agree has reached the heights of Michaelangelo or Stravinksy et al, but because I know that playing a video game can impact the way I see the world and I know that playing a board game can, to take just one example, grant me insight into the dynamics of multi-factional conflict that I could not have gotten any other way. And what's more I also know that those insights only happened because of years and years of dedicated work on the part of the designers who made them with exactly those intentions in mind. If those types of experiences haven't happened for you than I'm sorry. They are out there and available if you have the desire to explore them.

There is something differentiating in video games in the aspects of emergent gameplay (the systems of the game interacting with each other chaotically to produce complex results and narrative) and environmental storytelling (building a game world or level and telling a story by letting the player direct the camera themselves.)I was a huge fan of Roger Ebert's, and I remain a huge fan of his writing, but I do think he missed the mark on video game discourse. I would contend that, when the artist lets the player inject themselves into the work, it is precisely the artist's vision, because the artist has to create vectors for gameplay that offer intended consequences, and sometimes even unintended consequences, not unlike how great cinema gets interpreted and reinterpreted as film lovers find new resonances that the artist may not have considered at the outset.

A video game is not a landscape in which "all things are possible" for the player. Even the most malleable video game systems remain highly curated so that the player experiences what the developers want the player to experience. FromSoft may provide the player many routes through Elden Ring, but they cannot be said to lack vision simply because they've offered the player choices. Take one look around Limgrave and it becomes clear exactly how FromSoft wants you to navigate their game world. The same is true of Nintendo's Breath of the Wild. A very principled philosophy was applied to both of those games in pursuit of directing the player's pursuit of their own choices. The intensity of that vision is, in fact, so pronounced that it would require considerable effort to argue that neither of those games represents a strong artistic statement.

And all of that's before you even start breaking down specific elements of game development, like visual art direction, the crafting of individual game assets, sound design, musical composition, narrative structure, voice acting, etc. These may not be artistic elements that are exclusive to the world of video games... but so what? Cinema itself borrows heavily from the language of other mediums as it stakes out its artistic claims. Video games do the same.

Cinema inherently differentiates itself from other types of media via cinematography. To distinguish themselves artistically from cinema, games need to effectively use the ways in which they are differentiated in order to express themselves.

Do games use their differentiating qualities expressively? I think sometimes they do! There are good examples on this list. I am hopeful that this will continue, as I've invested a significant amount of my points into my identity as a gamer. I don't think this will continue if critics and consumers don't push game developers to take artistic risks.

I think you've got Ebert's argument correct, as far as I understand it. I'm hardly an Ebert scholar, but this debate was pretty spicy 10 years ago or so, it's something I tracked. I don't think it's supported that he wasn't writing in "good faith." He did acknowledge [later](https://www.rogerebert.com/roger-ebert/okay-kids-play-on-my-lawn) that he probably shouldn't be publicly judging video games if he isn't willing to play them, even if he never gave up his principled argument.Wow, I was rather dismissive of Ebert’s opinion on this when I thought it was simply narrow-minded and lacked foresight being confined to an era when video game stories were glorified Saturday Morning cartoons.

But what you just described is way, way worse.

The interactivity is what makes it not art? That artistic intent not only matters, but is the only thing that matters? Games will become art when they stop being games and become movies?

No strawman needed; That is not a good faith argument. That is a man desperately protecting his beloved artform from an up-and-coming artform he correctly feared would usurp it.

Let’s get this out of the way first: Every form of human expression is art. When I sing badly in the shower, when my pre-schooler scribbles what she claims is a unicorn on scratch paper with crayons, when a kid pisses his name in the snow. It’s all art. If prehistoric cave drawings can be described as early art, then everything is fair game. My goal is not to diminish art, but to expand, enrich, enable, and embolden all possible forms. It doesn’t matter what medium is used; what matters is the art’s ability to evoke emotion, elevate discussion, and inspire thought.

Basquiat’s entire mission statement was defiantly pushing non-art into high art spaces and demanding it be given authenticity. What would I think of a critic who dismissed Basquiat claiming street graffiti would never be true “art” until it started to look like the Mona Lisa?

So let’s all stop with this nonsense argument. This is not a question of defining terms; it’s a question of assigning value. The only way to interpret Ebert’s critique is to say video games are incapable of evoking, inspiring, and elevating, which inherently makes them less valuable. Art has value; everything else is a diversion, distraction, or really, a waste of time.

I know this to be emphatically untrue.

But these derisive and condescending arguments matter. They matter in convincing people the form in which you choose to express yourself matters more than the message you express. It matters in attempting to invalidate the very real connections and experiences people have with an artform not on the pre-approved list. And it matters in convincing creators they need to chase artificial benchmarks to achieve the all important authenticity.

How many games started trying to promote themselves as “cinematic” in an attempt to be taken seriously? How many games spent valuable and finite resources crafting cut scenes and quick-time events that could have gone toward game mechanics and world-building? How many games broke the bank on casting established Hollywood actors and motion capturing their likeness, while grinding their artists with crunch?

And I reject his patronizing and condescending “why do yo even need to be called art? There are lots of things that people spend their time on that aren’t “Art.” He might as well have patted me on the head and called me sport. If it’s unimportant, why did he feel the need to make the distinction?

It’s just a retread of the old hierarchical high art, low art, no art dynamic and frankly is quite tired and stodgy,

Interactivity and immersion is not a barrier to video games being seen as art. It is their greatest strength and the one component they have above all other artforms. There is an exhibit in LA right now attempt to do just that, and no one is dismissing them as “not art” as a result.

I respected Ebert’s film opinions, even when I disagreed with them. But here, he was purely wrong.

If all human activity is art, then sports as art, as well as commuting, and eating, and sleeping. There's nothing wrong with having this as a definition. It's self-consistent. And Ebert would be fine with all this too, as long as the expression was deliberate (by someone we call an "artist.). The problem with interactivity is that the game player becomes the artist, so large parts of the work itself become void of expressive value.

When the player enters the gameplay loop, the player is expressing themself, instead of interpreting someone else's vision. This is why Ebert makes the distinction, because besides the *principle* of having an artist's spark, he places a *value* on art as an empathy machine. It's difficult to hear someone else when you're focused on expressing yourself.

Löwenherz

Starter

Ebert's conclusion (the headline) was paired with a weaker argument than his own, that's a strawman. The article you linked is a rebuttal; to a criticism; of his argument, it doesn't actually contain his original point of view. One ought to work a bit to understand someone's point of view in order to refute it. Don't dig up someone's grave just to take a crap in it.

There is something differentiating in video games in the aspects of emergent gameplay (the systems of the game interacting with each other chaotically to produce complex results and narrative) and environmental storytelling (building a game world or level and telling a story by letting the player direct the camera themselves.)

Cinema inherently differentiates itself from other types of media via cinematography. To distinguish themselves artistically from cinema, games need to effectively use the ways in which they are differentiated in order to express themselves.

Do games use their differentiating qualities expressively? I think sometimes they do! There are good examples on this list. I am hopeful that this will continue, as I've invested a significant amount of my points into my identity as a gamer. I don't think this will continue if critics and consumers don't push game developers to take artistic risks.

I think you've got Ebert's argument correct, as far as I understand it. I'm hardly an Ebert scholar, but this debate was pretty spicy 10 years ago or so, it's something I tracked. I don't think it's supported that he wasn't writing in "good faith." He did acknowledge [later](https://www.rogerebert.com/roger-ebert/okay-kids-play-on-my-lawn) that he probably shouldn't be publicly judging video games if he isn't willing to play them, even if he never gave up his principled argument.

If all human activity is art, then sports as art, as well as commuting, and eating, and sleeping. There's nothing wrong with having this as a definition. It's self-consistent. And Ebert would be fine with all this too, as long as the expression was deliberate (by someone we call an "artist.). The problem with interactivity is that the game player becomes the artist, so large parts of the work itself become void of expressive value.

When the player enters the gameplay loop, the player is expressing themself, instead of interpreting someone else's vision. This is why Ebert makes the distinction, because besides the *principle* of having an artist's spark, he places a *value* on art as an empathy machine. It's difficult to hear someone else when you're focused on expressing yourself.

I reject outright that artistic intention is not only primarily important, but paramount. I think it is a key aspect when discussing a work to better understand the purpose of elements used, why they’re present, how they’re expected to work together, and what themes are being explored. But to even suggest the artist’s intentions are all that matter and any involvement or interaction by the audience voids expressive value borders on paternalistic.

The audience is not a passive member of artistic expression. Quite actually, their interpretations and engagement are precisely what elevates it.

When I read a novel, I don’t passively absorb the words on the page. I interact, engage, attack, question, create. I create my own images in my head of who these characters are and what worlds they inhabit, which is of course informed by the artist, but ultimately is a creation of my own and independent of the countless other worlds envisioned by every reader of that same author’s work. According to this narrow reading of Ebert’s critique, the moment the images in my head differ from what the author intended, then it is either failed art, or not art at all.

When I gaze at a painting, I am inspired to craft stories in my head of what’s going on, who the people are, their backstories, what kind of world is being presented, or what kinds of sounds and sensations I might experience if the painting is abstract.

Similar situations arise with music, sculptures, and yes, film.

I appreciate Ebert being open about his lack of experience with video games. But it does shift his argument wholly uninformed.

A player is not “creating art” by exploring the worlds the creators have designed for them. They are engaging with the art in the same way they would any other form.

Last edited:

Löwenherz

Starter

Ebert's conclusion (the headline) was paired with a weaker argument than his own, that's a strawman. The article you linked is a rebuttal; to a criticism; of his argument, it doesn't actually contain his original point of view. One ought to work a bit to understand someone's point of view in order to refute it. Don't dig up someone's grave just to take a crap in it.

There is something differentiating in video games in the aspects of emergent gameplay (the systems of the game interacting with each other chaotically to produce complex results and narrative) and environmental storytelling (building a game world or level and telling a story by letting the player direct the camera themselves.)

Cinema inherently differentiates itself from other types of media via cinematography. To distinguish themselves artistically from cinema, games need to effectively use the ways in which they are differentiated in order to express themselves.

Do games use their differentiating qualities expressively? I think sometimes they do! There are good examples on this list. I am hopeful that this will continue, as I've invested a significant amount of my points into my identity as a gamer. I don't think this will continue if critics and consumers don't push game developers to take artistic risks.

I think you've got Ebert's argument correct, as far as I understand it. I'm hardly an Ebert scholar, but this debate was pretty spicy 10 years ago or so, it's something I tracked. I don't think it's supported that he wasn't writing in "good faith." He did acknowledge [later](https://www.rogerebert.com/roger-ebert/okay-kids-play-on-my-lawn) that he probably shouldn't be publicly judging video games if he isn't willing to play them, even if he never gave up his principled argument.

If all human activity is art, then sports as art, as well as commuting, and eating, and sleeping. There's nothing wrong with having this as a definition. It's self-consistent. And Ebert would be fine with all this too, as long as the expression was deliberate (by someone we call an "artist.). The problem with interactivity is that the game player becomes the artist, so large parts of the work itself become void of expressive value.

When the player enters the gameplay loop, the player is expressing themself, instead of interpreting someone else's vision. This is why Ebert makes the distinction, because besides the *principle* of having an artist's spark, he places a *value* on art as an empathy machine. It's difficult to hear someone else when you're focused on expressing yourself.

Also, it’s your turn.

I honestly can't think of a "sports" game (other than racing?) that I really enjoyed playing. I know it's a video game, but the few I tried were just so disconnected from the sport itself I never got into it. Basketball, football, hockey, whatever. The game play just looked and acted so fake (or disconnected?) compared to the real thing.I legitimately cannot believe this is still on the board, specifically due to the demographic of this board and the main reason why we all post here, basketball.

I am a die hard sports gamer and can only say NBA Jam is an arcade game that has some basketball elements. I do prefer games that make genuine effort to feel like their sports, often times this tends to favor them having weaker graphics and presentation which is at least partially why I stopped buying them annually in the mid-00s.I honestly can't think of a "sports" game (other than racing?) that I really enjoyed playing. I know it's a video game, but the few I tried were just so disconnected from the sport itself I never got into it. Basketball, football, hockey, whatever. The game play just looked and acted so fake (or disconnected?) compared to the real thing.

Ebert's conclusion (the headline) was paired with a weaker argument than his own, that's a strawman. The article you linked is a rebuttal; to a criticism; of his argument, it doesn't actually contain his original point of view. One ought to work a bit to understand someone's point of view in order to refute it. Don't dig up someone's grave just to take a crap in it.

There is something differentiating in video games in the aspects of emergent gameplay (the systems of the game interacting with each other chaotically to produce complex results and narrative) and environmental storytelling (building a game world or level and telling a story by letting the player direct the camera themselves.)

Cinema inherently differentiates itself from other types of media via cinematography. To distinguish themselves artistically from cinema, games need to effectively use the ways in which they are differentiated in order to express themselves.

Do games use their differentiating qualities expressively? I think sometimes they do! There are good examples on this list. I am hopeful that this will continue, as I've invested a significant amount of my points into my identity as a gamer. I don't think this will continue if critics and consumers don't push game developers to take artistic risks.

I think you've got Ebert's argument correct, as far as I understand it. I'm hardly an Ebert scholar, but this debate was pretty spicy 10 years ago or so, it's something I tracked. I don't think it's supported that he wasn't writing in "good faith." He did acknowledge [later](https://www.rogerebert.com/roger-ebert/okay-kids-play-on-my-lawn) that he probably shouldn't be publicly judging video games if he isn't willing to play them, even if he never gave up his principled argument.

If all human activity is art, then sports as art, as well as commuting, and eating, and sleeping. There's nothing wrong with having this as a definition. It's self-consistent. And Ebert would be fine with all this too, as long as the expression was deliberate (by someone we call an "artist.). The problem with interactivity is that the game player becomes the artist, so large parts of the work itself become void of expressive value.

When the player enters the gameplay loop, the player is expressing themself, instead of interpreting someone else's vision. This is why Ebert makes the distinction, because besides the *principle* of having an artist's spark, he places a *value* on art as an empathy machine. It's difficult to hear someone else when you're focused on expressing yourself.

And you've made no effort to understand my point of view, so what are we doing here? Are we not allowed to disagree with the man once he's died? What is it that you think I accused him of which is offensive? That he probably shouldn't have been talking about video games as art when he didn't play them? You just linked to an article where he admitted that about himself.

And I didn't strawman his argument, I paraphrased it. I was trying to be charitable and acknowledge that he was basing that argument on a more limited understanding of what a "game" is than most of us actual game players would use today. Personally, I really like reading Ebert's reviews even when I don't agree with all of his points because he's a good writer and he's always expressing his own truth, not what he thinks someone else wants to hear.

Speaking of which, in that same article he also said this:

"I thought about those works of Art that had moved me most deeply. I found most of them had one thing in common: Through them I was able to learn more about the experiences, thoughts and feelings of other people. My empathy was engaged. I could use such lessons to apply to myself and my relationships with others. They could instruct me about life, love, disease and death, principles and morality, humor and tragedy. They might make my life more deep, full and rewarding."

My whole argument for why a game can be called art even when allowing for player agency is that a game designer can deliberately and intentionally put the player in a position where they are able to experience empathy for another human or group of humans or another living thing. And furthermore, because the player is discovering that point of view on their own through their own choices and through the execution of game mechanics rather than watching a narrative, the experience of empathy can actually be more powerful than being shown/told someone else's point of view through a song or a movie. And if that's what the game designer is doing, intentionally, how is that different than any other artist which fulfills Ebert's gold standard of engaging his empathy?

I'm currently in the process of designing a WWI themed boardgame and I took a year and a half off from working on it to do more research exclusively on the Armenian genocide because I didn't think the game was complete without it and I didn't think I knew enough at that point to treat the subject with the care it deserves. My goal in this is not to tell the player anything, it's to construct a game system which simulates the actual circumstances of a person who was put into the same role so that by grappling with that system and making choices purely on strategic grounds (or not) they have the opportunity to be complicit in committing acts of genocide. It's a small part of the overall game but the amount of thought and effort that I've put into getting that one detail right has been enormous.

In fact, when I think about every choice that I've made over the last 6 years of working on this game they have all been aimed at exactly what Roger Ebert described in that quote above about the art that moves him the most. The whole point of making this game at all is to help people to understand more about the experiences, thoughts, and feelings of other people. Granted a board game isn't the same as a video game but they rely on a lot of the same principles. And I find it insulting for anyone to imply that games might be considered art but only if we broaden the definition so much as to include any human activity.

Even if the game player becomes the artist by making choices within the framework I've created (a premise that I do not agree with), I've still put those guard rails (the rules) there for a reason to guide their hand. And if those rules came about through my own distillation of thousands of pages of reading and hundreds of hours spent with a graphics editing program designing the user interface and a hundred more hours observing how other people interact with the systems and tweaking them to better fit the story I want to tell, you're telling me that my game is void of expressive value because rather than telling you something with it I've created a gadget that you can play with and discover those lessons for yourself? That's nonsense.

You could just as well say that the film critic is more of an artist than the filmmaker because the movie simply is what it is -- the emotions that a viewer draws from it are their own. I think we would both agree that anyone who said that doesn't understand what a movie is. And similarly, I think that anyone who says a game player is merely expressing themselves and not learning anything from the structure of the rules of play with which they are engaged doesn't actually understand what a game is.

Löwenherz

Starter

Ebert's conclusion (the headline) was paired with a weaker argument than his own, that's a strawman. The article you linked is a rebuttal; to a criticism; of his argument, it doesn't actually contain his original point of view. One ought to work a bit to understand someone's point of view in order to refute it. Don't dig up someone's grave just to take a crap in it.

There is something differentiating in video games in the aspects of emergent gameplay (the systems of the game interacting with each other chaotically to produce complex results and narrative) and environmental storytelling (building a game world or level and telling a story by letting the player direct the camera themselves.)

Cinema inherently differentiates itself from other types of media via cinematography. To distinguish themselves artistically from cinema, games need to effectively use the ways in which they are differentiated in order to express themselves.

Do games use their differentiating qualities expressively? I think sometimes they do! There are good examples on this list. I am hopeful that this will continue, as I've invested a significant amount of my points into my identity as a gamer. I don't think this will continue if critics and consumers don't push game developers to take artistic risks.

I think you've got Ebert's argument correct, as far as I understand it. I'm hardly an Ebert scholar, but this debate was pretty spicy 10 years ago or so, it's something I tracked. I don't think it's supported that he wasn't writing in "good faith." He did acknowledge [later](https://www.rogerebert.com/roger-ebert/okay-kids-play-on-my-lawn) that he probably shouldn't be publicly judging video games if he isn't willing to play them, even if he never gave up his principled argument.

If all human activity is art, then sports as art, as well as commuting, and eating, and sleeping. There's nothing wrong with having this as a definition. It's self-consistent. And Ebert would be fine with all this too, as long as the expression was deliberate (by someone we call an "artist.). The problem with interactivity is that the game player becomes the artist, so large parts of the work itself become void of expressive value.

When the player enters the gameplay loop, the player is expressing themself, instead of interpreting someone else's vision. This is why Ebert makes the distinction, because besides the *principle* of having an artist's spark, he places a *value* on art as an empathy machine. It's difficult to hear someone else when you're focused on expressing yourself.

I really want to make sure you aren’t feeling ganged up on. I understand you as working to clarify Ebert’s position, not necessarily expressing your own.

Besides, Dwarf Fortress, among roughly 40 other games, have been displayed in a dedicated collection at MoMA in New York since Ebert offered his opinion, so I’m figuring that pretty much closes the book on this discussion.

Looking forward to your next pick. Make it artsy.

Insomniacal Fan

Starter

Satisfactory -- 2024 -- PC

I have been provoked into adding yet another factory game to my list!

The setup of Satisfactory is very similar to Factorio. You take on the role of a "Pioneer" sent down all by yourself to industrialize a remote planet. The Pioneer accomplishes this task by exploring the world for resources, exploiting those resources, using those resources to develop a network of factories, and researching new technologies that allow them to continue to do this even more expansively and effectively.

The first big difference from Factorio, is this is all done in a very large (if not open) game world from a first-person perspective, instead of the top-down from Factorio. The second big difference, is that the world of Satisfactory is hand designed (instead of procedurally generated), and it is *beautiful*

As you're looking around the world for resources to exploit, you'll wander through epic vistas, rolling hills, exotic alien forests, etc. Exploring the world is like taking a hike through a magical wilderness, with every tree placed thoughtfully by an artist, and 360 degree postcard quality landscapes surrounding you at all times.

And then you start placing factories, and you feel the satisfaction of getting an automation line up. You place a happy little factory next to a babbling brook populated by a bunch of little critters. The GLADOS style AI directs you towards making more complex parts, you start connecting factories together. The conveyors that stitch together your factories start to become a bit of an eyesore, but it's fine, you can reorganize later, once you reach your next production quota. Your production line scales up, and after reaching a set of milestones you get more cool toys with which to interact with the world, and a new set of milestones.

You survey all that you have accomplished

What have I done in the name of progress! Conveyor belts spread out like spaghetti, trapping wildlife within. The happy little trees placed by the game's artists tend to sprout from areas that are a bit inconvenient, so we chop those down as we go. The spread of factories creeps like a bright orange shiny metallic fungus across the landscape. And the horizons are broken up by power lines.

Maybe at this point you start thinking about how to aesthetically design your factories so they aren't so ugly, maybe you lean into the objectives to try and unlock the next toy that's going to fix the previous sprawl. Or maybe you try to maximize the exploitation of every resource, clear cutting the landscape to make the most mega factory possible. Maybe you just do what seems natural, and recline into the game loop of exploring, planning, building and connecting (the game is very relaxing, and the in game timer to remind players to step away from the computer every couple of hours is well placed.) The game itself doesn't judge you.

I think Satisfactory is an example of how to artfully use the flow state to criticize how we can become simple machines when rewarded exactly right. I think it points out how engagement with a goal oriented decision loop can be a trap instead of an enriching experience. I think it works as an environmental allegory, presenting an excellent case for the value of conserving the natural world even if it means people having less cool stuff.

I earnestly think it does all those things. But it wouldn't do any of these things very well if it wasn't a well designed game.

I have been provoked into adding yet another factory game to my list!

The setup of Satisfactory is very similar to Factorio. You take on the role of a "Pioneer" sent down all by yourself to industrialize a remote planet. The Pioneer accomplishes this task by exploring the world for resources, exploiting those resources, using those resources to develop a network of factories, and researching new technologies that allow them to continue to do this even more expansively and effectively.

The first big difference from Factorio, is this is all done in a very large (if not open) game world from a first-person perspective, instead of the top-down from Factorio. The second big difference, is that the world of Satisfactory is hand designed (instead of procedurally generated), and it is *beautiful*

As you're looking around the world for resources to exploit, you'll wander through epic vistas, rolling hills, exotic alien forests, etc. Exploring the world is like taking a hike through a magical wilderness, with every tree placed thoughtfully by an artist, and 360 degree postcard quality landscapes surrounding you at all times.

And then you start placing factories, and you feel the satisfaction of getting an automation line up. You place a happy little factory next to a babbling brook populated by a bunch of little critters. The GLADOS style AI directs you towards making more complex parts, you start connecting factories together. The conveyors that stitch together your factories start to become a bit of an eyesore, but it's fine, you can reorganize later, once you reach your next production quota. Your production line scales up, and after reaching a set of milestones you get more cool toys with which to interact with the world, and a new set of milestones.

You survey all that you have accomplished

What have I done in the name of progress! Conveyor belts spread out like spaghetti, trapping wildlife within. The happy little trees placed by the game's artists tend to sprout from areas that are a bit inconvenient, so we chop those down as we go. The spread of factories creeps like a bright orange shiny metallic fungus across the landscape. And the horizons are broken up by power lines.

Maybe at this point you start thinking about how to aesthetically design your factories so they aren't so ugly, maybe you lean into the objectives to try and unlock the next toy that's going to fix the previous sprawl. Or maybe you try to maximize the exploitation of every resource, clear cutting the landscape to make the most mega factory possible. Maybe you just do what seems natural, and recline into the game loop of exploring, planning, building and connecting (the game is very relaxing, and the in game timer to remind players to step away from the computer every couple of hours is well placed.) The game itself doesn't judge you.

I think Satisfactory is an example of how to artfully use the flow state to criticize how we can become simple machines when rewarded exactly right. I think it points out how engagement with a goal oriented decision loop can be a trap instead of an enriching experience. I think it works as an environmental allegory, presenting an excellent case for the value of conserving the natural world even if it means people having less cool stuff.

I earnestly think it does all those things. But it wouldn't do any of these things very well if it wasn't a well designed game.

Last edited:

Insomniacal Fan

Starter

I reject outright that artistic intention is not only primarily important, but paramount. I think it is a key aspect when discussing a work to better understand the purpose of elements used, why they’re present, how they’re expected to work together, and what themes are being explored. But to even suggest the artist’s intentions are all that matter and any involvement or interaction by the audience voids expressive value borders on paternalistic.

The audience is not a passive member of artistic expression. Quite actually, their interpretations and engagement are precisely what elevates it.

When I read a novel, I don’t passively absorb the words on the page. I interact, engage, attack, question, create. I create my own images in my head of who these characters are and what worlds they inhabit, which is of course informed by the artist, but ultimately is a creation of my own and independent of the countless other worlds envisioned by every reader of that same author’s work. According to this narrow reading of Ebert’s critique, the moment the images in my head differ from what the author intended, then it is either failed art, or not art at all.

When I gaze at a painting, I am inspired to craft stories in my head of what’s going on, who the people are, their backstories, what kind of world is being presented, or what kinds of sounds and sensations I might experience if the painting is abstract.

Similar situations arise with music, sculptures, and yes, film.

I appreciate Ebert being open about his lack of experience with video games. But it does shift his argument wholly uninformed.

A player is not “creating art” by exploring the worlds the creators have designed for them. They are engaging with the art in the same way they would any other form.

I don't think Ebert was against active audience engagement, he was a film critic after all, that's basically all he did. And an artist's perspective being necessary does not imply an artist's interpretation is supreme.

I am glad it's clear that that is what I'm attempting to do. I am normally a once a week poster, so it is a bit challenging for me to keep upI really want to make sure you aren’t feeling ganged up on. I understand you as working to clarify Ebert’s position, not necessarily expressing your own.

Besides, Dwarf Fortress, among roughly 40 other games, have been displayed in a dedicated collection at MoMA in New York since Ebert offered his opinion, so I’m figuring that pretty much closes the book on this discussion.

Looking forward to your next pick. Make it artsy.

For what it's worth, I'm convinced Ebert is on to something in being skeptical of the value of engaging with a game loop, and more broadly, I think games are hurt more by gamer self-satisfaction than they are by diminishment by cultural critics.

Ebert did predict games would end up in a museum in his first post in the topic around 2006, replicated here

Barker is right that we can debate art forever. I mentioned that a Campbell’s soup could be art. I was imprecise. Actually, it is Andy Warhol’s painting of the label that is art. Would Warhol have considered Clive Barker’s video game “Undying” as art? Certainly. He would have kept it in its shrink-wrapped box, placed it inside a Plexiglas display case, mounted it on a pedestal, and labeled it “Video Game.”

Insomniacal Fan

Starter

There's a lot of interesting posts on here, I could write a reply to every game one of the hundreds of game recommendations. I understand it's frustrating to not get engagement after putting effort into something. But I'm not a very prolific poster, so I have to prioritize. Just keeping up with my picks is a significant load for me.And you've made no effort to understand my point of view, so what are we doing here? Are we not allowed to disagree with the man once he's died? What is it that you think I accused him of which is offensive? That he probably shouldn't have been talking about video games as art when he didn't play them? You just linked to an article where he admitted that about himself.

And I didn't strawman his argument, I paraphrased it. I was trying to be charitable and acknowledge that he was basing that argument on a more limited understanding of what a "game" is than most of us actual game players would use today. Personally, I really like reading Ebert's reviews even when I don't agree with all of his points because he's a good writer and he's always expressing his own truth, not what he thinks someone else wants to hear.

Past that, correcting misconceptions is a high priority for me. I don't object to you criticizing someone living or dead, I objected to you getting the criticism wrong and spreading it. Whether Ebert likes it or not, his criticism is historically notable. For what it's worth, I don't think you needed to invoke the guy anyway to talk about what you wanted to talk about.

Good luck with the game! It's a hard thing to discuss hard things, whatever the medium. But there are examples of games handling serious topics like genocide and war artfully.My whole argument for why a game can be called art even when allowing for player agency is that a game designer can deliberately and intentionally put the player in a position where they are able to experience empathy for another human or group of humans or another living thing. And furthermore, because the player is discovering that point of view on their own through their own choices and through the execution of game mechanics rather than watching a narrative, the experience of empathy can actually be more powerful than being shown/told someone else's point of view through a song or a movie. And if that's what the game designer is doing, intentionally, how is that different than any other artist which fulfills Ebert's gold standard of engaging his empathy?

I'm currently in the process of designing a WWI themed boardgame and I took a year and a half off from working on it to do more research exclusively on the Armenian genocide because I didn't think the game was complete without it and I didn't think I knew enough at that point to treat the subject with the care it deserves. My goal in this is not to tell the player anything, it's to construct a game system which simulates the actual circumstances of a person who was put into the same role so that by grappling with that system and making choices purely on strategic grounds (or not) they have the opportunity to be complicit in committing acts of genocide. It's a small part of the overall game but the amount of thought and effort that I've put into getting that one detail right has been enormous.

In fact, when I think about every choice that I've made over the last 6 years of working on this game they have all been aimed at exactly what Roger Ebert described in that quote above about the art that moves him the most. The whole point of making this game at all is to help people to understand more about the experiences, thoughts, and feelings of other people. Granted a board game isn't the same as a video game but they rely on a lot of the same principles. And I find it insulting for anyone to imply that games might be considered art but only if we broaden the definition so much as to include any human activity.

Even if the game player becomes the artist by making choices within the framework I've created (a premise that I do not agree with), I've still put those guard rails (the rules) there for a reason to guide their hand. And if those rules came about through my own distillation of thousands of pages of reading and hundreds of hours spent with a graphics editing program designing the user interface and a hundred more hours observing how other people interact with the systems and tweaking them to better fit the story I want to tell, you're telling me that my game is void of expressive value because rather than telling you something with it I've created a gadget that you can play with and discover those lessons for yourself? That's nonsense.

You could just as well say that the film critic is more of an artist than the filmmaker because the movie simply is what it is -- the emotions that a viewer draws from it are their own. I think we would both agree that anyone who said that doesn't understand what a movie is. And similarly, I think that anyone who says a game player is merely expressing themselves and not learning anything from the structure of the rules of play with which they are engaged doesn't actually understand what a game is.

Padrino

All-Star

Do games use their differentiating qualities expressively? I think sometimes they do! There are good examples on this list. I am hopeful that this will continue, as I've invested a significant amount of my points into my identity as a gamer. I don't think this will continue if critics and consumers don't push game developers to take artistic risks.

I'd argue that they often do so, and there are a dozen examples within this very draft, and dozens of examples beyond it. Furthermore, it would seem like folly to contend that video gaming as a medium needs to somehow bat a higher percentage than other mediums in order to be taken seriously as artistic expression. There are more movies released each year that do not use their differentiating qualities expressively than there are movies that do so, with directors who simply point the camera at the actors in alternating close-ups and instruct them to say the words from the script. We all know what these movies look like and they are not what we would generally refer to as "cinema". But the medium is not invalidated as a whole because of the fact that most movies are commercially-motivated rather than artistically-motivated.

I'd also like to hammer home the point that video games and movies are both mixed media. They possess differentiating qualities unique to themselves, yes, but they are utterly reliant on elements borrowed from other mediums in order to achieve the full weight of their expression. Ridley Scott's Blade Runner was a landmark film for its art direction and cinematography. Scott and his DoP, Jordan Cronenweth, did absolutely masterful work on that movie. Still, Blade Runner possesses half its resonance without Vangelis' incredible musical score. And hilariously, one of the most affecting pieces in the film, "Memories of Green", wasn't even an original composition for the movie. It was from an album Vangelis released a couple of years prior. Yet nobody looks at Blade Runner today and thinks less of it because it possessed such a monumental and influential film score, despite the fact that music has no intrinsic value to the medium of filmmaking. It began as a silent medium, after all.

Elsewhere, Martin Scorsese has always been king of the needle drop. I don't see anybody readying to revoke Scorsese's auteur card even though he's frequently relied on popular music to shape the stories he tells. The Lord of the Rings films are themselves an adaptation of a significant literary work, but who's being moved by those movies without Howard Shore's powerful themes guiding their emotional experience? Is filmmaking a lesser medium than literature because the words on the page can stand alone? What about a giant like John Williams? Without Williams, our pop cultural landscape would look mightily different, and we'd be worse off for his absence. But there's not some massive marketplace of people dying to listen to Williams' scores separate from the filmed experiences to which they're attached. As gifted as he's always been, Spielberg's career doesn't reach the rafters without Williams. Were the cynics right? Is Spielberg not an artist but instead a purveyor of cheap thrills?

Löwenherz

Starter

Satisfactory -- 2004 -- PC

I have been provoked into adding yet another factory game to my list!

The setup of Satisfactory is very similar to Factorio. You take on the role of a "Pioneer" sent down all by yourself to industrialize a remote planet. The Pioneer accomplishes this task by exploring the world for resources, exploiting those resources, using those resources to develop a network of factories, and researching new technologies that allow them to continue to do this even more expansively and effectively.

The first big difference from Factorio, is this is all done in a very large (if not open) game world from a first-person perspective, instead of the top-down from Factorio. The second big difference, is that the world of Satisfactory is hand designed (instead of procedurally generated), and it is *beautiful*

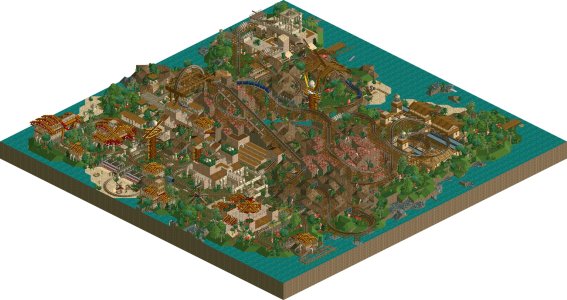

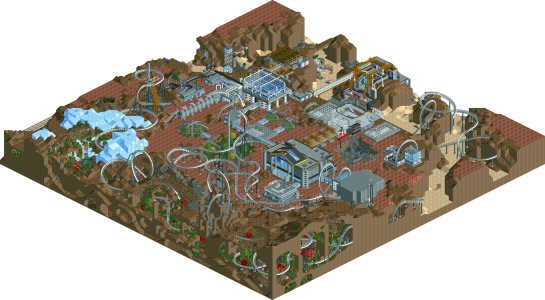

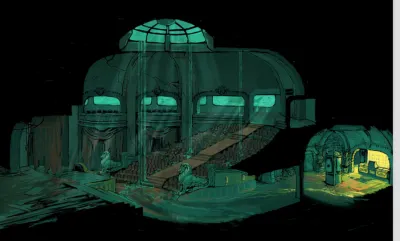

View attachment 14059

View attachment 14060View attachment 14061

As you're looking around the world for resources to exploit, you'll wander through epic vistas, rolling hills, exotic alien forests, etc. Exploring the world is like taking a hike through a magical wilderness, with every tree placed thoughtfully by an artist, and 360 degree postcard quality landscapes surrounding you at all times.

And then you start placing factories, and you feel the satisfaction of getting an automation line up. You place a happy little factory next to a babbling brook populated by a bunch of little critters. The GLADOS style AI directs you towards making more complex parts, you start connecting factories together. The conveyors that stitch together your factories start to become a bit of an eyesore, but it's fine, you can reorganize later, once you reach your next production quota. Your production line scales up, and after reaching a set of milestones you get more cool toys with which to interact with the world, and a new set of milestones.

You survey all that you have accomplished

View attachment 14062

View attachment 14063

What have I done in the name of progress! Conveyor belts spread out like spaghetti, trapping wildlife within. The happy little trees placed by the game's artists tend to sprout from areas that are a bit inconvenient, so we chop those down as we go. The spread of factories creeps like a bright orange shiny metallic fungus across the landscape. And the horizons are broken up by power lines.

Maybe at this point you start thinking about how to aesthetically design your factories so they aren't so ugly, maybe you lean into the objectives to try and unlock the next toy that's going to fix the previous sprawl. Or maybe you try to maximize the exploitation of every resource, clear cutting the landscape to make the most mega factory possible. Maybe you just do what seems natural, and recline into the game loop of exploring, planning, building and connecting (the game is very relaxing, and the in game timer to remind players to step away from the computer every couple of hours is well placed.) The game itself doesn't judge you.

I think Satisfactory is an example of how to artfully use the flow state to criticize how we can become simple machines when rewarded exactly right. I think it points out how engagement with a goal oriented decision loop can be a trap instead of an enriching experience. I think it works as an environmental allegory, presenting an excellent case for the value of conserving the natural world even if it means people having less cool stuff.

I earnestly think it does all those things. But it wouldn't do any of these things very well if it wasn't a well designed game.

Oooh, pretty.

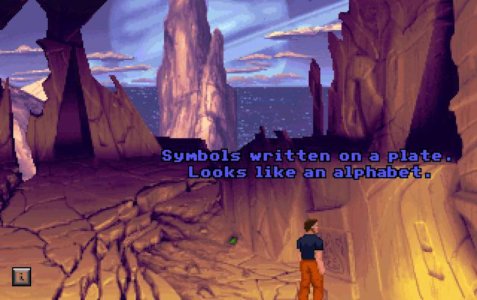

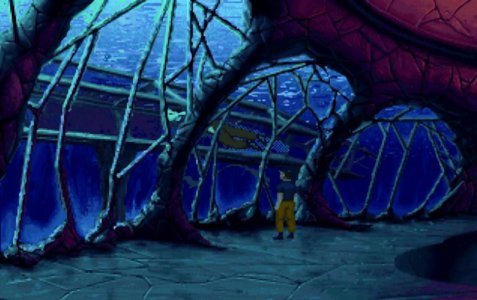

Format: PC

Year of Release: 1995

Developer: LucasArts

Genre: Point and Click Adventure

Why I picked it: Art Design & Nostalgia

If you haven't got the idea by now that I'm a hopeless aesthete when it comes to all forms of visual media, here's 9 more frames of faded pastel-hued mid 90s pixel art to really drive the point home. Like @Padrino , I am a sucker for any game with an eye-catching and internally consistent visual style and The Dig certainly makes an impression with its art design. The LucasArts point and click adventure game was a whole genre unto itself stretching from the late 1980s to the early 2000s. Unique amongst their catalog, though, was The Dig's somewhat incongruous mixture of the familiar cartoon aesthetic employed by that legendary design studio with a super serious philosophical sci-fi tone. Most dismissed this game upon release as a disappointment -- a game stuck too long in development hell and saddled with some of the corniest video game dialog ever recorded. But for me (and a few like-minded diehards) this stands out as the apex of that very productive time period in the golden age of adventure games.

The Dig was marketed with one name at the top of every print ad so I might as well bullet it up front too -- from the mind of Steven Spielberg. In the mid 90s that name was instant box office gold and yes he did have some tangential involvement in the story scripting process but probably not as much as the top billing implies. Initially this was to be a spin-off of a TV series idea which was never filmed -- a story about competing archeologists on an alien world. Three lead designers and as many abandoned half-finished attempts later, the eventual finished game features an opening plot about a mission to blow up a giant asteroid heading toward Earth which quickly takes things in a decidedly more Carl Sagan direction than the two big-budget films which mined the same dramatic territory several years later. And so our cast of three finds themselves stranded on a seemingly abandoned alien planet with only a few tools to start putting together a self-rescue plan.

The rest of the game sees you in the role of Commander Boston Low tinkering with alien gadgets and trying to decipher your unseen hosts' weird hieroglyphic language. Actually most of the translation work is left to your cranky co-worker Maggie Robbins to do off-screen -- yet when you finally get to speak to an alien for the first time it's the Commander who does all the talking. Hmm, I think I understand why Ms. Robbins is so cranky. The main thrust of the story involves an addictive substance which has life giving properties and takes us through some plot beats borrowed from the John Huston classic Treasure of the Sierra Madre -- I suppose that's where The Dig earns its title? This storyline is the game's strongest quality and it ultimately leads to one of the more shocking moments I experienced in a game up to that point, though by today's standards it's pretty tame. I won't spoil it though in case anyone reading this might want to have the experience for themselves.

On a personal note, this is another game that I can't help but remember as a shared experience -- my brother and I taking turns being stumped by some of the more obtuse of the games many puzzles. There is a lot of Myst in this game, right down to the "who in their right mind would ever think up that solution on their own" resolution to two of the game's most annoying puzzles. This is another of my old childhood favorites that I have long earmarked as a potential movie or TV show idea (a re-birth really in this case since it was supposed to be a TV show to begin with) but that process of adaptation involves inventing about 80% of the story. What's here is compelling but it amounts to little more than a killer setup and a handful of translatable set-pieces. Also the ending isn't great. All of that walking around and clicking on stuff just won't hit the same on a big screen.

Speaking of big screens, since this was developed on the Skywalker Ranch as a pet project for Steven Spielberg to indulge in his love for video games, there is also another first here which to my knowledge has not been repeated on any other title before or since. Some of the cut-scenes in The Dig -- all of the scenes where we watch a blue hamster-ball shaped vehicle traveling between the five main spires that make up the game world -- were created by staff at Industrial, Light, and Magic. Think of the mine car chase at the end of Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom but with much blockier rendering and no dramatic tension at all. Whee!

And as always, I've saved the best for last -- it might just be nostalgia speaking but of course I'm going to say that the music here is fantastic as well and adds a lot to the overall experience. This is another computer game for which I've bought the soundtrack CD and I actually do listen to this one quite a bit when I'm in the mood for something ethereal, haunting, and dripping with Casio keyboard charm. Credit to composer Michael Land for finding the right aural accompaniment to hours of walking around rocky spires in perpetual twilight feeling confused.

I'm sure I've oversold the magnificence of this game. There is more "you had to be there" about my love for The Dig's many quirks and my willingness to look past the flaws than is true of any of the other picks I've made so far. This game arrived in my life in teaser form as a playable demo of the first 15 or so minutes packaged with a 3D rendered virtual tour of a futuristic Dodge dealership. Yes, really! That initial taste of a few pixelated and charmless astronauts stuck on a strange alien world was enough to hook me back then and it's still enough for me to add it to my personal library of virtual comfort food. Would it be enough to keep anyone else's attention among the millions of other entertainment options available now? Perhaps not. Nonetheless, I'm really happy to make this my 10th pick and sail right past the irony of drafting not just one but two games about wandering around on deserted islands with which to populate my own hypothetical desert island.

Format: PC

Year of Release: 1999

Developer: Chris Sawyer

Genre: Strategy / Economic Simulation

Why I picked it: Infinite Sandbox Tool

My gaming collection would not be complete without some kind of sandbox game to use as a blank canvas for making things. And so I can't put it off any longer, I've got to take the one game which has consumed more hours of my life (by far) than any other and that's the original RollerCoaster Tycoon. On the surface this is an economic simulation game about building and running your own theme park. You need to research new ride designs, set your admission price, pay for ad campaigns to bring guests into your park, place lots of concessions stands and restrooms, hire staff to keep everything clean, and so on. It all gets pretty granular -- right down to the placement of each tree, flower, bench, light pole, and trash can. And of course the main attraction here -- the E Ticket so to speak -- is that you design each rollercoaster piece by piece like the world's greatest toy train set is at your fingertips. I mean, you do have to use a mouse but the analogy still applies.

So that's what the game is about and it's one of the best selling PC games of all time because it's easy for anyone to play and there's enough depth in the variety of scenarios and ride types to keep you entertained for quite a long time. It's a bit like that other enormously popular sandbox game from the following year but for people who are more interested in civil engineering than orchestrating their own reality show. I played RollerCoaster Tycoon (RCT for short) in the way it was intended to be played for about a year and it was fun but would have grown stale if not for three circumstances:

(1) This game came out in 1999, just as the internet was taking off as a place to form virtual communities like the one we find ourselves in now.

(2) Clever fans made and shared tools through these communities which manipulated the Hexadecimal code of the game, allowing for innovations like using the game's terrain stacking engine in combination with rollercoaster pieces to create impressionistic architecture.

(3) I was already crazy about rollercoasters and theme parks as a teenager and wanted desperately to design my own.

And from that perfect storm of circumstances emerged an obsession. I created my first online persona (Coaster Ed) and started my first website (Ed's Coasters International). Like most budding RCTers in the early 2000s (we called ourselves Parkmakers) I stumbled across the fan site of a professional visual effects artist (Danimation.com) which spotlighted a fan created park every month and started dreaming about one day achieving my own featured spotlight park (I eventually did -- though that park is no longer available online). Dan himself lost interest in the game in time and so we spun-off into a new RCT community called New Element (nedesigns.com). For the next 7 or so years until I "retired" and moved on, this was the only game I played and I played it almost every day. I won some community awards, made virtual friends all over the world, and even some real-life friends (mostly because we all went to the same school) that I would take road trips with to all of the California theme parks.

Rather than try to describe this game any further, I'd just like to show you pictures of some of the stuff I made with it...

(Click on each map thumbnail to zoom in)

I give this one to Tarantino, but I agree with your point here. It was quite literally 30 years ago that I took my single film studies course at university and I recall a similar point being made when discussing early cinema.Elsewhere, Martin Scorsese has always been king of the needle drop.

Padrino

All-Star

Format: PC

Year of Release: 1999

Developer: Chris Sawyer

Genre: Strategy / Economic Simulation

Why I picked it: Infinite Sandbox Tool

My gaming collection would not be complete without some kind of sandbox game to use as a blank canvas for making things. And so I can't put it off any longer, I've got to take the one game which has consumed more hours of my life (by far) than any other and that's the original RollerCoaster Tycoon. On the surface this is an economic simulation game about building and running your own theme park. You need to research new ride designs, set your admission price, pay for ad campaigns to bring guests into your park, place lots of concessions stands and restrooms, hire staff to keep everything clean, and so on. It all gets pretty granular -- right down to the placement of each tree, flower, bench, light pole, and trash can. And of course the main attraction here -- the E Ticket so to speak -- is that you design each rollercoaster piece by piece like the world's greatest toy train set is at your fingertips. I mean, you do have to use a mouse but the analogy still applies.

So that's what the game is about and it's one of the best selling PC games of all time because it's easy for anyone to play and there's enough depth in the variety of scenarios and ride types to keep you entertained for quite a long time. It's a bit like that other enormously popular sandbox game from the following year but for people who are more interested in civil engineering than orchestrating their own reality show. I played RollerCoaster Tycoon (RCT for short) in the way it was intended to be played for about a year and it was fun but would have grown stale if not for three circumstances:

(1) This game came out in 1999, just as the internet was taking off as a place to form virtual communities like the one we find ourselves in now.

(2) Clever fans made and shared tools through these communities which manipulated the Hexadecimal code of the game, allowing for innovations like using the game's terrain stacking engine in combination with rollercoaster pieces to create impressionistic architecture.

(3) I was already crazy about rollercoasters and theme parks as a teenager and wanted desperately to design my own.

And from that perfect storm of circumstances emerged an obsession. I created my first online persona (Coaster Ed) and started my first website (Ed's Coasters International). Like most budding RCTers in the early 2000s (we called ourselves Parkmakers) I stumbled across the fan site of a professional visual effects artist (Danimation.com) which spotlighted a fan created park every month and started dreaming about one day achieving my own featured spotlight park (I eventually did -- though that park is no longer available online). Dan himself lost interest in the game in time and so we spun-off into a new RCT community called New Element (nedesigns.com). For the next 7 or so years until I "retired" and moved on, this was the only game I played and I played it almost every day. I won some community awards, made virtual friends all over the world, and even some real-life friends (mostly because we all went to the same school) that I would take road trips with to all of the California theme parks.

Rather than try to describe this game any further, I'd just like to show you pictures of some of the stuff I made with it...

View attachment 14075 View attachment 14076 View attachment 14077 View attachment 14078

(Click on each map thumbnail to zoom in)

View attachment 14079 View attachment 14080 View attachment 14081 View attachment 14082

Nice pick! I made a list of 50 games for this particular draft, and between my own picks and many others that have come off the board, it looks like I have about 25 or so remaining. This one was among them, and I wasn't sure if I was going to select it or not, so I'm glad it's represented in our draft.

Insomniacal Fan

Starter

For my next pick, another with the theme of economics and industrialization, but this time in SPACE!

X4: Foundations -- 2018 -- PC

I'm struggling with how to describe this game. Egosoft, the developers, also seem to have trouble doing so. Their YouTube page has several tries at a "What is X4?" explainer video. I'll give it a shot here.

Visually it's a spaceship shooter, inspired by Star Wars, with various ships and fighter craft flying around, pew-pewing each other with abandon. But The spaceship combat isn't really the point of the game, despite all the assets and artwork that visualize it.

The game world is a set of ~150 space systems interconnected by a set of portals. Each of the systems has a cool skybox, some interesting asteroids and/or gas clouds, and maybe some unique ambient theme music. There is an in-game map, but it starts out completely blank, so exploration is part of the game initially. Visiting all of the universe's systems would take hours, but there is a finite quantity, these are hand-designed, so eventually the player can discover everything. And while it's kind of neat to discover new art, the game isn't really an art gallery.

In (nearly all of) the systems there are stations that you can dock with and walk around on. There are traders on board that you can sell space junk to, and some rudimentary crafting stations. At some stations there are consoles to upgrade your vessels with tricked-out equipment. You can take missions with NPCs; some of which are scripted stories that affect the broader universe and deliver a narrative, and those missions will take you across the X universe. But the production value on these quests is very shoestring. The voice direction is... minimalistic. These scripted missions constitute the cinematic aspect of this game, and the presentation is so half-assed that it's clear this isn't the focus of the game.

The stations produce and consume goods, refining raw ore and gas collected from asteroids and clouds, into refined materials, which are transported by freighters from one station to another. The traffic generated by the freighters transiting goods from one place to another make up the majority of NPCs you make up. The buy and sell prices of the various commodities will dynamically change depending on the current supply at the station, if a station's export warehouse is full, then the station will lower the cost to incentivize external freighters to buy from them. If a station is in short supply of a necessary component of the good it manufactures, it will raise its buy price to attract traders on that end. And *this* is absolutely the heart of the game.

---

Everything in the game depends on the dynamic economy, and if it breaks down, then the AI freighters and the player will compete with each other to fill shortages and fix it. If you have your eyes on a fancy new gun for your ship, and the local economy is scarce of a component of that gun, then you are simply S.O.L. until you or the AI figures out what's wrong with the supply chain and fixes it. Maybe you need a shipment of exotic resources from across the galaxy, maybe it means patrolling a trade corridor from pirates and hostile factions. Perhaps you need to build your own factory to fill the manufacturing demands of a local system.

To make this work, the entire X universe is continuously being simulated. This has profound consequences. If you take an action like interdicting trade yourself, the consequences can chaotically spiral out to affect the entire X Universe; rampaging evil aliens could wipe out a faction and turn them into grey goo because you decided to pirate a freighter of silicon wafers for your own purposes. There are some game systems that try to stabilize the world, but they can be broken. And it's impossible to predict exactly how the universe will develop over time.

Imagine doing the game design for this, trying to tweak the rules of the game so that the player has a good time hanging out in your fundamentally chaotic game world. Anyway, here are some screenshots of space ships.

X4: Foundations -- 2018 -- PC

I'm struggling with how to describe this game. Egosoft, the developers, also seem to have trouble doing so. Their YouTube page has several tries at a "What is X4?" explainer video. I'll give it a shot here.

Visually it's a spaceship shooter, inspired by Star Wars, with various ships and fighter craft flying around, pew-pewing each other with abandon. But The spaceship combat isn't really the point of the game, despite all the assets and artwork that visualize it.

The game world is a set of ~150 space systems interconnected by a set of portals. Each of the systems has a cool skybox, some interesting asteroids and/or gas clouds, and maybe some unique ambient theme music. There is an in-game map, but it starts out completely blank, so exploration is part of the game initially. Visiting all of the universe's systems would take hours, but there is a finite quantity, these are hand-designed, so eventually the player can discover everything. And while it's kind of neat to discover new art, the game isn't really an art gallery.

In (nearly all of) the systems there are stations that you can dock with and walk around on. There are traders on board that you can sell space junk to, and some rudimentary crafting stations. At some stations there are consoles to upgrade your vessels with tricked-out equipment. You can take missions with NPCs; some of which are scripted stories that affect the broader universe and deliver a narrative, and those missions will take you across the X universe. But the production value on these quests is very shoestring. The voice direction is... minimalistic. These scripted missions constitute the cinematic aspect of this game, and the presentation is so half-assed that it's clear this isn't the focus of the game.

The stations produce and consume goods, refining raw ore and gas collected from asteroids and clouds, into refined materials, which are transported by freighters from one station to another. The traffic generated by the freighters transiting goods from one place to another make up the majority of NPCs you make up. The buy and sell prices of the various commodities will dynamically change depending on the current supply at the station, if a station's export warehouse is full, then the station will lower the cost to incentivize external freighters to buy from them. If a station is in short supply of a necessary component of the good it manufactures, it will raise its buy price to attract traders on that end. And *this* is absolutely the heart of the game.

---

Everything in the game depends on the dynamic economy, and if it breaks down, then the AI freighters and the player will compete with each other to fill shortages and fix it. If you have your eyes on a fancy new gun for your ship, and the local economy is scarce of a component of that gun, then you are simply S.O.L. until you or the AI figures out what's wrong with the supply chain and fixes it. Maybe you need a shipment of exotic resources from across the galaxy, maybe it means patrolling a trade corridor from pirates and hostile factions. Perhaps you need to build your own factory to fill the manufacturing demands of a local system.

To make this work, the entire X universe is continuously being simulated. This has profound consequences. If you take an action like interdicting trade yourself, the consequences can chaotically spiral out to affect the entire X Universe; rampaging evil aliens could wipe out a faction and turn them into grey goo because you decided to pirate a freighter of silicon wafers for your own purposes. There are some game systems that try to stabilize the world, but they can be broken. And it's impossible to predict exactly how the universe will develop over time.

Imagine doing the game design for this, trying to tweak the rules of the game so that the player has a good time hanging out in your fundamentally chaotic game world. Anyway, here are some screenshots of space ships.

Last edited:

macadocious

Starter

Tet kinda stole my thunder by taking a more recent version of this game, but I love this game. This is the OG for the series

Format: PS2

Year of Release: 2001

Developer: Naughty Dog

Genre: Platform/Action Adventure

Why I picked it: It mixes my favorite video game genres

Again, early 2000s is around when I stopped playing video games (regularly). My son was born in 2005, and even though I played some after that, it wasn't a lot. Running a business and having small children really didn't leave a lot of time for this anymore, unless I wanted to ignore my wife. That probably wasn't a good idea.

I have beaten this game twice. It's just a fun game. It's like if Zelda, Mario and Sonic were all combined into a 3d game. You have simple game play, platforms but it's not landscape and basic functions of jumping and fighting. There are also times you get to operate vehicles. To me, this is what video games are/should be. A lighthearted fun action game.

Per Wiki:

@Sluggah

Format: PS2

Year of Release: 2001

Developer: Naughty Dog

Genre: Platform/Action Adventure

Why I picked it: It mixes my favorite video game genres

Again, early 2000s is around when I stopped playing video games (regularly). My son was born in 2005, and even though I played some after that, it wasn't a lot. Running a business and having small children really didn't leave a lot of time for this anymore, unless I wanted to ignore my wife. That probably wasn't a good idea.

I have beaten this game twice. It's just a fun game. It's like if Zelda, Mario and Sonic were all combined into a 3d game. You have simple game play, platforms but it's not landscape and basic functions of jumping and fighting. There are also times you get to operate vehicles. To me, this is what video games are/should be. A lighthearted fun action game.

Per Wiki:

Jak's basic actions include running, jumping, double-jumping, crouching, and ledge-grabbing. Jak can also perform a rolling jump to reach distant platforms.<a Jak's combat moves include a spin attack, a dash-punch, a dive attack, and an uppercut.Jak has unlimited lives and three hit points, which are depleted by enemy attacks or contact with environmental hazards. Losing all three hit points triggers a death animation and a comment from Daxter before the player respawns in the beginning of the last section of the area they were located in.

@Sluggah

Sluggah

All-Star

Title: Lumines: Puzzle Fusion

Format: PSP

Year of Release: 2004

Developer: Q Entertainment

As a launch title for a handheld device, Lumines absolutely knocked it out of the park. Fun, addictive, the vibiest soundtrack…time completely melts away when playing. You could hop on a plane, bust out Lumines, then be startled by a flight attendant telling you to put your tray table away for landing 5 hours later. I know this from experience.

SLAB

Hall of Famer

Pick 11: Red Dead Redemption (PS3)

Couldn’t go an entire list without an open R* sandbox game. And I’m going with one whose story I adore. RDR’s stories are so much better to play than GTA’s whose characters I always find obnoxious and grating. Without fail.

Meanwhile over here, I love John Marston. A great lead. A great environment. A fun new mechanic with the Deadahot ability. A great story told. So much good stuff here. I actually just replayed this after beating RDR2 a little while back, and it holds up amazingly well.

BioShock

Developer: 2K Games

Year: 2007

Platform: PC

I kind of picked up this FPS game on a whim way back when and, well, it was just plain awesome.

A few quick snippets from wiki as they say it a lot better than I can:

BioShock received universal acclaim and was particularly praised by critics for its narrative, themes, visual design, setting, and gameplay. It is considered to be one of the greatest video games ever made and a demonstration of video games as an art form.

BioShock has received "universal acclaim", according to review aggregator Metacritic, with the game receiving an average review score of 96/100 for Xbox 360 and Microsoft Windows, and 94/100 for PlayStation 3. Mainstream press reviews have praised the immersive qualities of the game and its political dimension.

The Chicago Sun-Times review said "I never once thought anyone would be able to create an engaging and entertaining video game around the fiction and philosophy of Ayn Rand, but that is essentially what 2K Games has done ... the rare, mature video game that succeeds in making you think while you play".

The New York Times reviewer described it as: "intelligent, gorgeous, occasionally frightening" and added: "Anchored by its provocative, morality-based story line, sumptuous art direction and superb voice acting, BioShock can also hold its head high among the best games ever made."

It has been noted that the combination of the game's elements "straddles so many entertainment art forms so expertly that it's the best demonstration yet how flexible this medium can be. It's no longer just another shooter wrapped up in a pretty game engine, but a story that exists and unfolds inside the most convincing and elaborate and artistic game world ever conceived."

BioShock has received praise for its artistic style and compelling storytelling. In their book, Digital Culture: Understanding New Media, Glen Creeber and Royston Martin perform a case study of BioShock as a critical analysis of video games as an artistic medium. They praised the game for its visuals, sound, and ability to engage the player into the story. They viewed BioShock as a sign of the "coming of age" of video games as an artistic medium.