In response to talent evaluators, just like anything else in life it seems to me that the standard for who gets a job is rarely who is the most qualified. We've seen a lot of Kings front offices blow a lot of draft picks. A poorly run organization may be hiring the wrong people, not listening to them, failing to provide them the resources needed for them to do their jobs effectively, etc. Probably all of the above.

You are using a statistical model to grade an end product (VORP) which makes no account of anything that happens between the draft and the sum total of a player's career. Obviously the situations are different but what is the same about the draft model you've proposed and the hypothetical production studio scenario I proposed as an analogy is what I am intending to communicate to you. If you have a statistical model which takes point A and point Z and eliminates everything in between as irrelevant, I feel personally that I cannot determine anything useful from that model. You also seem dismissive of the concept of an analogy in general. It's simply a rhetorical tool to communicate a concept without getting bogged down in trying to first agree on all of the relevant terminology involved. I'm not going to try to use the terminology of statistical analysis with you because I don't know the definitions of those words precisely enough not to bungle them.

The concept of "best player available" is itself a misleading phrase. In order to know that definitively you would have to know the future. Ah, but you say, we do know the future! At least in regard to players from past drafts, right? No we don't. We know one small slice of it -- what happens when each player is drafted to one particular team. That makes up a tiny percentage of the possible outcomes. I would call that statistically insignificant in relation to the percentages of possible outcomes which are not represented. And that's what you're basing all of your data on. We say we want the BPA but since we're talking about players who then need to be part of a team, their fit is always relevant to outcome. Tyrese Haliburton, for instance, may finish his career as the best player by VORP from the 2020 draft. Your model would credit the Kings for drafting him even though nearly all of his career will have been played somewhere else. Why would a team trade a player they deemed BPA in the draft less than 2 years into his career? Roster balance, a desire to compete sooner, maximizing the value of another player who plays the same position. In short: fit.

This reads to me like you're just assuming your own conclusion. If I'm picking at #6 what do I care that most BPA are picked in the top 5? I'm not interested in most, I'm interested in who do I pick at #6. I get that this whole exercise is meant to point out that according to you if I'm not picking at #1-5 then I'm more or less screwed. Or at least I think that's what this was about. I think what it actually shows is that NBA teams on average are pretty good about determining who the top 5 most talented players are in a given draft year if not the precise order. And the typical talent distribution of a single draft class is such that the remaining 55 players taken are much more dependent on the fit situation in order to find success in the NBA. So if I were a front office executive, I would spend my time and energy focusing on what I can control which is: (1) the process I'm using to determine who will succeed in my team situation both in the immediate future and long-term and (2) all of the other factors which make up that team situation in the first place.

Compressing this quite a bit; I'm not looking at this from the perspective of a front office exec or a talent scout, I'm looking at it from the position as a fan.

As a fan, it's useful for me to know whether the team is headed in a good direction or a wrong direction.

As a fan, one thing I don't assume is that I can judge from the outside how good or bad a given front office is, as so much of those decisions are internal, and as you pointed out, teams replace their front offices every 5 years or so. The

least presumptuous position to take is that the front office is average, so I'm measuring likely outcomes based on average performance.

I have already granted that I am assuming that teams picking in the top 5 are looking for BPA instead of best fit. (If you're picking in the top 5, it's generally expected that your team sucks, and you don't have other pieces you're trying to build around, that's the whole point of the draft.) Corollary to that is the assumption that BPA exists, that some players are simply better at being pro basketball players than others (again, why even have a draft if this weren't at least somewhat true?) I'm curious how much you'd push the opposite belief.

If you're picking at #6, then hopefully you're doing it as part of a multi-year project to rebuild, or you're already on the upswing after nabbing a franchise cornerstone type player previously. Because there's usually only one or two players that rise to that level every year. In order to feel happy about it as a fan, you're probably going to need to zoom out and have a longer term outlook.

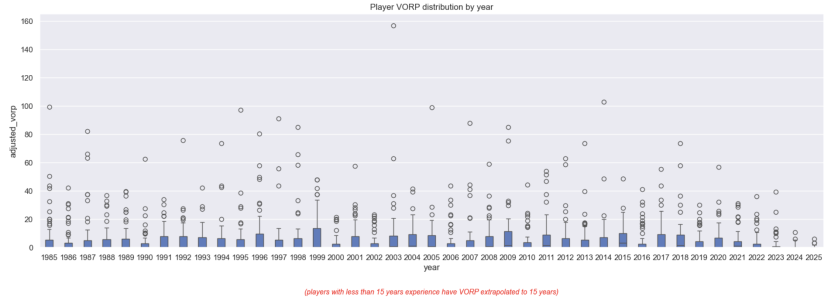

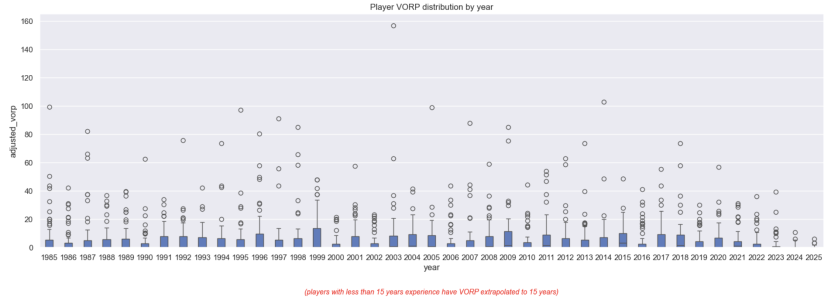

(I don't think there's anything particularly impressive about VORP compared to other career impact metrics, it was just conveniently available, and seemed to correlate with my intuition in dividing very good careers from great careers. Take it for what it's worth.)

And I don't have any particular problem with analogies as an explanatory tool. Often complex concepts are usefully explained in terms of the dynamics of simplified systems, (sports analogies are popular!) But if we're already talking about a topic that's used for simplified examples, it's of dubious value. At that level, I suspect the analogy is less about explanation, and more about obfuscation.